The Persian Empire was not a single kingdom but a magnificent succession of empires that ruled the vast Iranian plateau—known as Irān, the “Land of the Aryans”—and stretched far beyond it. The earliest known Persian dynasty, the Achaemenids (648–330 BCE), united various Aryan tribes under one banner and built the first truly great empire of Iran. This empire, which began in what is now Fars Province, rose under the vision and leadership of Cyrus the Great, whose name still echoes through history as one of the most admired rulers of the ancient world.

Western historians often refer collectively to all pre-1935 Iranian dynasties as the “Persian Empire.” But the Persian story is much more than a label; it’s a chronicle of human ambition, innovation, and cultural achievement that shaped much of the ancient world.

Iran today stands as the 18th most populous nation on Earth, a regional powerhouse and a vital player in both Middle Eastern and global politics. Yet modern news often focuses on the nation’s challenges — nuclear disputes, political tensions, and social struggles — overshadowing its glorious past.

Centuries ago, this land was known as Persia, one of the mightiest civilizations in history. In the 6th century BCE, the Persian Empire was the second-largest empire ever known, its vast influence extending from the Indus Valley in the east to Northern Greece and Egypt in the west. This was not just a political power; it was a civilization that introduced new concepts of governance, human rights, architecture, and trade — contributions that still shape our world today.

The chronicle of Ancient Persia begins with the Achaemenid Empire in the mid-6th century BCE, which thrived until Alexander the Great’s conquest in 330 BCE. Yet Persia’s fall did not mean its disappearance. Strategically located along the world’s most vital trade routes between East and West, the region continued to be a cornerstone of global culture and politics.

Understanding modern Iran requires looking back at its deep historical roots — the ancient kingdoms that once ruled the world, the philosophies and religions born here, and the empires that shaped both Asia and Europe.

Where Was Ancient Persia Located?

The term Persia once referred to the territory that we now know as the modern-day nation of Iran. Situated just east of the Persian Gulf, this landmass forms part of the Iranian Plateau, a region rich in mountains, deserts, and fertile valleys that allowed civilizations to flourish for thousands of years.

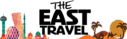

The first Persian capital, Pasargadae, was founded in the 7th century BCE in what is now Fars Province, southern Iran. From here, the early Persian kings began to unite neighboring tribes under one banner. Later, magnificent cities such as Persepolis and Susa emerged — political and ceremonial centers that stood as architectural masterpieces of their time.

Pasargadae was more than a capital; it symbolized the unity of the Persian people. Persepolis, with its monumental staircases and stone carvings, became the ceremonial heart of the empire, while Susa, strategically positioned near Mesopotamia, evolved into a hub of administration and commerce.

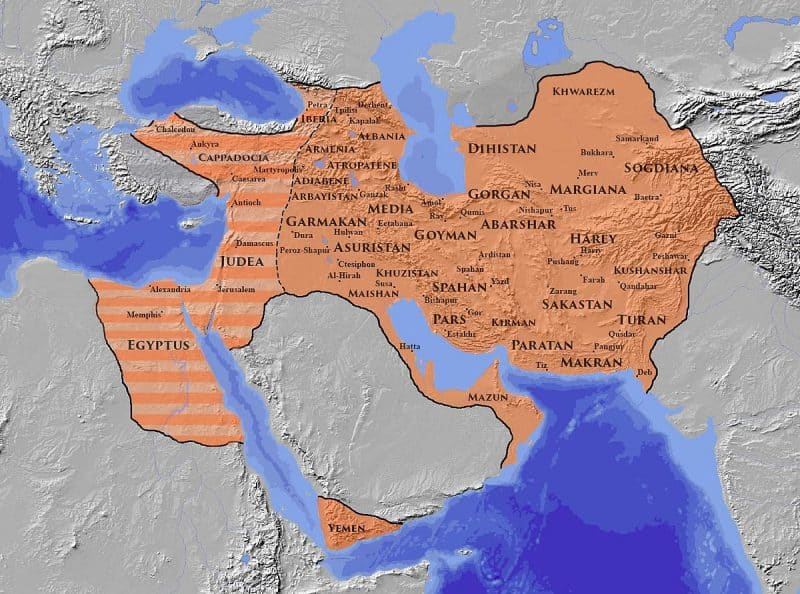

At its height, the Persian Empire covered nearly all of Mesopotamia, along with parts of present-day Egypt, Turkey, Greece, Armenia, Turkmenistan, and Afghanistan. The empire’s reach was vast — stretching across three continents — and its impact was equally enduring.

The map of the Persian Empire reveals an astonishing scale: red stars mark Susa in the north, Persepolis in the center, and Pasargadae further south — the triad of power that defined ancient Persia.

The Persian People

The Persians were a branch of the broader Iranian peoples, an ethnolinguistic family that spoke various dialects of the Iranian language. They are believed to have migrated to the Iranian plateau around the 10th century BCE, likely descending from Aryan tribes originating in the steppes of northern Europe and Central Asia.

Their language, Old Persian, belonged to the Indo-European family, linking it distantly to languages as diverse as Hindi, Greek, German, and English. This linguistic lineage reflects how Persian culture, though distinctly Eastern, shared deep roots with other early Indo-European civilizations.

Today, Persian identity remains deeply connected to its language, Farsi, and its cultural heritage. About half of Iran’s population identifies as Persian — roughly 25 million people — but Persian-speaking communities also thrive in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan. Over the centuries, Persia’s cultural and intellectual influence spread widely, touching everything from philosophy and art to science and governance.

Many of Persia’s most celebrated poets, scholars, and kings were born outside modern Iran, illustrating the vastness of Persian civilization. To be “Persian” has always been more about shared culture and language than geographic boundaries — a concept that helped the empire maintain unity across such a large and diverse territory.

The Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire marked the true beginning of Persia’s greatness — a dynasty that not only unified the Iranian plateau but expanded it into the largest empire of its age. Founded by Cyrus II, later known as Cyrus the Great, this era transformed Persia into a model of governance, architecture, and cultural tolerance.

Cyrus was the great-great-grandson of Achaemenes, the first Persian ruler whose name gave the dynasty its title. When Cyrus became king in 559 BCE, he ruled little more than a modest collection of tribes in southern Iran. Yet within decades, his vision and strategy reshaped the world.

Cyrus first defeated the Medes, another powerful Iranian people who controlled much of northern and western Iran. By 550 BCE, he had unified the two nations and turned his attention to other empires — Lydia in modern Turkey and Babylonia, the ancient center of Mesopotamia. By 547 BCE, both had fallen under Persian control, and Cyrus stood as the ruler of the largest empire humanity had ever seen.

Ancient Persia Trivia #1

At its height, the Achaemenid Empire spanned 5.5 million square kilometers — an area so vast that, if it existed today, it would be the 7th largest nation on Earth, roughly double the size of Argentina and nearly rivaling Australia.

Cyrus’s rule was remarkable not only for its military success but also for its humanity. Unlike many conquerors, he believed in mercy and respect. Historical records, including the Cyrus Cylinder, often called the first declaration of human rights, show that he allowed conquered peoples to retain their customs and religions. In the Biblical Book of Isaiah, Cyrus is praised for releasing Jewish captives from Babylon and allowing them to return home — an act that cemented his legacy as a just and enlightened ruler.

After Cyrus’s death, his son Cambyses II carried the empire’s expansion even further, conquering Egypt, Libya, and parts of Greece by 525 BCE. Under the Achaemenids, Persia became not only a political empire but a crossroads of cultures — the world’s first experiment in global governance.

The Rise of Darius I

When Cambyses II died suddenly in 522 BCE, Persia plunged into chaos. With no direct heir, a brief civil struggle erupted until Darius I, known as Darius the Great, claimed the throne. Though distantly related to the royal line, Darius proved to be one of Persia’s most capable rulers.

He left behind one of history’s most important inscriptions, carved into the rock face at Mount Behistun in western Iran. Written in Elamite, Old Persian, and Babylonian, this trilingual record detailed his lineage, victories, and the divine right that legitimized his rule.

The image depicts Darius the Great on the Greek Darius vase, discovered in 1851 in Canosa di Puglia, Naples.

Darius reorganized the empire’s administration through a revolutionary system of satrapies, or provinces, each governed by a satrap — a regional governor entrusted with immense power but loyal to the king. This system allowed Persia to maintain control over its vast and diverse lands efficiently.

He also began the construction of the Royal Road, an ancient highway stretching more than 2,700 kilometers, linking Susa to Sardis. This road became the lifeline of the empire, enabling swift communication, trade, and military movement.

Darius’s Reign Marked Three Major Achievements:

-

The Satrap System: By decentralizing power while maintaining loyalty to the crown, Darius built a model of governance that many later empires imitated.

-

The Greco-Persian Wars: His ambition to expand westward brought Persia into direct conflict with Greece, setting the stage for one of the most legendary confrontations in ancient history.

-

Susa as the Capital: He established Susa as a central capital, strategically located along trade routes to ensure better administrative control.

Darius’s reign solidified Persia’s place as the most advanced empire of its era — a powerhouse of culture, economy, and political organization.

The Greco-Persian Wars

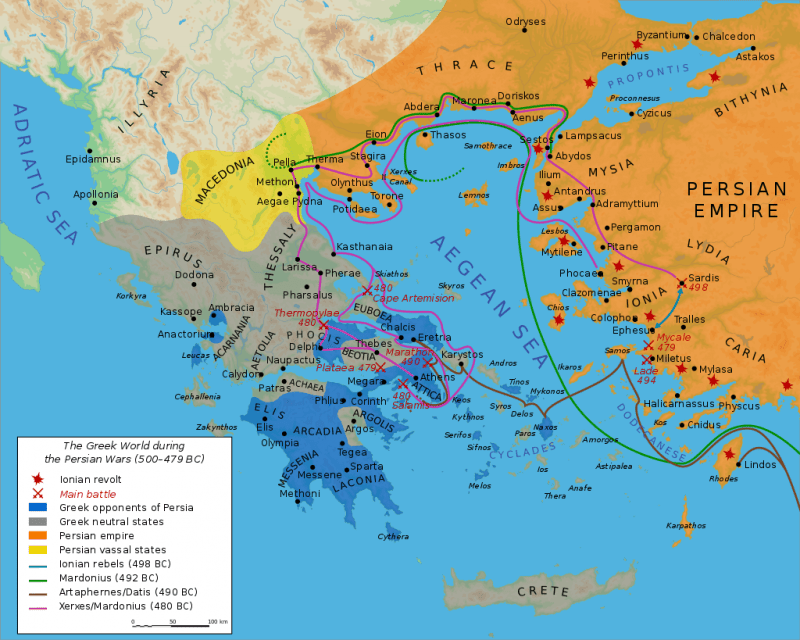

By the late 6th century BCE, Darius sought to extend Persia’s dominion into Greece, then a patchwork of independent city-states rich in culture but divided politically. His first attempt to invade Greece failed due to internal revolts and a disastrous campaign led by the Greek tyrant Aristagoras, sparking the Ionian Revolt (499–493 BCE).

Despite suppressing the rebellion, Darius vowed revenge. In 490 BCE, he launched a massive invasion, sending fleets from Egypt and Phoenicia across the Aegean. They captured the city of Eritrea but were halted by the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon — a stunning victory for Athens that became one of the defining moments of Western history.

Although Darius planned another invasion, his death in 487 BCE halted the campaign.

Ancient Persia Trivia #2

At its zenith, the Persian Empire governed 44% of the world’s population — nearly 50 million people. To match that today, a single government would have to rule China, India, the United States, and Indonesia combined.

Xerxes’ Ascent and the Road to Thermopylae

When Xerxes I inherited the throne after Darius I, his first years were consumed by stabilizing the empire. Rebellions flared on its margins, and the machinery of government demanded constant attention. But by 480 BCE, urged on by advisers and the lingering memory of Marathon, Xerxes resolved to complete what his father had begun: a decisive conquest of Greece.

He gathered one of antiquity’s largest expeditionary forces—ancient sources give extravagant figures, but even conservative estimates suggest well over a hundred thousand troops—and paired it with a powerful Phoenician and Egyptian fleet. The plan was audacious: sweep down the Thracian coast, force the narrow land passages into central Greece, and break Athenian and Spartan resistance in one coordinated blow.

At first, momentum favored Persia. Xerxes bridged the Hellespont, carved a canal through Athos to protect his fleet, and advanced with the systematic inevitability of empire. Yet the Greeks chose their ground well. At Thermopylae, a Spartan-led force under Leonidas stalled the Persian advance in a legendary stand; though the pass was ultimately taken, the delay proved costly. Soon after, Greek naval strategy hit its stride, and the tide turned at Salamis, followed by decisive defeats of Persian land forces at Plataea and the allied naval victory at Mycale. Xerxes’ grand design unraveled; the empire remained immense, but its westward expansion was checked—permanently.

The campaign map of Xerxes’ invasion shows both the ambition and the vulnerability of vast empires: long supply lines, narrow chokepoints, and determined local resistance could blunt even the greatest military machine of its age.

Timeline After Xerxes: Later Achaemenid Rulers

After Xerxes, the Achaemenid Empire shifted from sweeping conquest to maintenance and management. Its later kings grappled with internal succession issues, restless provinces, and the persistent challenge posed by Greek city-states.

-

Artaxerxes I (c. 467–424 BCE)

Continued the long shadow conflict with the Greeks, much of it fought indirectly in Egypt, where Athenian-backed rebellions strained Persian authority. His reign culminated in the Peace of Callias (traditionally dated to the 440s–450 BCE), which stabilized relations and recognized spheres of influence. -

Artaxerxes II (c. 412–358 BCE)

Came to power amid a murky succession and widespread unrest. He quelled rebellions and preserved the core of the empire but lost a firm grip on Egypt. Intrigue within the royal court and pressure at the frontiers underscored how difficult it had become to govern so vast a domain. -

Artaxerxes III (c. 358–338 BCE)

Engineered a brief resurgence. He reconquered Egypt and pushed back in Asia Minor, strengthening imperial defenses. Yet the uneasy balance with the Greeks—now increasingly influenced by Macedon—left the empire exposed to a new, rising power. -

Artaxerxes IV, Darius III, and Artaxerxes V (Bessus) (c. 338–330 BCE)

A tumultuous endgame. Artaxerxes IV reigned briefly and was killed amid instability. Darius III faced Alexander of Macedon and suffered decisive defeat at Gaugamela (331 BCE). In the chaos that followed, the satrap Bessus (Artaxerxes V) betrayed Darius, seized a royal title he could not hold, and was soon captured and executed. The Achaemenid chapter closed as Alexander the Great assumed control, but Persia’s civilizational story continued under new banners.

Persian Faith: Zoroastrianism

Long before Islam, Persia’s spiritual horizon was defined by Zoroastrianism, often regarded as the earliest monotheistic faith. Founded by the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster)—commonly dated between the 2nd and 1st millennium BCE—it matured into state tradition during the Achaemenid era and later became the official religion under Artaxerxes II.

At its core, Zoroastrianism teaches a cosmic duality: the struggle between Asha (Truth/Order) aligned with Ahura Mazda (“Wise Lord”), and Druj (Lie/Chaos). Humans, endowed with moral agency, participate in this struggle through their choices. Salvation is not passive; it’s woven from conduct in daily life.

Three succinct principles capture the Zoroastrian ethic:

-

Humata, Hukhta, Huvarshta — Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds.

-

There is one path: Truth (Asha) is the measure of action.

-

Do what is right because it is right—reward follows as consequence, not bribe.

Zoroastrian ideas about ethical monotheism, judgment, and the ultimate triumph of good resonated far beyond Iran, influencing later religious thought. Though diminished after the Islamic conquests, the faith endures among communities in Iran and India (the Parsis). Its cultural footprint remains visible—from fire temples and funerary practices to echoes in philosophy (Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra) and the life stories of modern figures raised in Zoroastrian households.

Persia After the Achaemenids: Parthians and Sassanids

Alexander’s whirlwind conquests folded Persia into a Hellenistic world, first under Seleucid rule. But imperial gravity did not rest forever outside Iran. By the 3rd century BCE, the Parthians—an Iranian royal house from the northeast—asserted autonomy, established their own capital, and slowly reconsolidated Persian heartlands, including Susa, Persepolis, and Pasargadae.

Parthian strategy emphasized cavalry warfare, mobile archery, and flexible diplomacy—a necessary posture against their principal rival: Rome. Though neither side fully mastered the other, famous engagements—like Carrhae (53 BCE)—proved Parthian martial prowess and preserved Iran’s independence.

By 224 CE, a new Iranian dynasty, the Sassanids, rose from Fars. With a reenergized administrative system, a revitalized Zoroastrian clergy, and a sharpened military edge, they forged a second golden age of Persian power. Against the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire, the Sassanids waged seesaw wars, at times reaching the gates of Constantinople and annexing territories in the Levant and Egypt. Their cultural and political confidence re-centered Iran as a great power of Late Antiquity.

Ancient Persia Trivia #4

Ancient Persians were practical innovators at home—even keeping hedgehogs as household helpers to curb insects. Everyday ingenuity underpinned the grandeur: small solutions sustaining large civilizations.

Culture in Bloom: The Sassanid Age

Sassanid Iran became a cosmopolitan marketplace of goods and ideas, positioned astride the arteries linking India, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean. Workshops thrived: metalwork, rock reliefs, stucco, and especially textiles gained international fame. The iconic Simurgh, a benevolent mythical bird, soared across silks and tapestries, symbolizing luck, sovereignty, and renewal.

This era also shaped the visual grammar that later informed Islamic art—arabesques, intricate vegetal motifs, monumental epigraphy, and a taste for rhythmic geometry. The courtly culture of the Sassanids—its etiquette, ceremonial, and patronage—left durable legacies from architecture to literature, echoing across centuries of Persianate courts from Transoxiana to the Deccan.

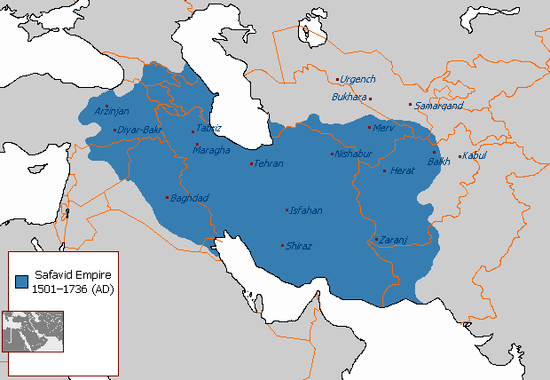

The Safavid Dynasty

After the Arab conquests (7th century CE) transformed Iran’s religious landscape and integrated it into the Dar al-Islam, new Persian polities rose in cycles. Among them, the Safavids (1501–1722) stand out for forging a cohesive Iranian state and canonizing Twelver Shi‘ism as its religious foundation—decisions that still shape Iran’s identity.

The Safavids frequently contested borders with the Ottoman Empire, forming a durable geopolitical frontier that approximates modern Iran’s western bounds. As one of the Gunpowder Empires—with the Ottomans and Mughals—Safavid Iran harnessed firearms, fortifications, and centralized bureaucracy to consolidate power. Cities like Isfahan blossomed into capitals of urban beauty: grand squares, bridges, gardens, and mosques that married engineering with aesthetics.

The Qajar Dynasty

The Qajars (1789–1925) inherited a world redefined by European sea power and industrial finance. They restored sovereignty over a recognizable Iranian core and initiated modernization—from military reform to nascent industry—yet struggled against Russian and British encroachment. Concessions, capitulations, and debt entanglements fostered public criticism and seeded anti-imperial sentiment that would echo deep into the 20th century.

Still, the period saw crucial developments: the Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) curbed absolute monarchy and introduced a parliament (Majles), modern legal codes, and a public sphere alive with newspapers and debate. Iran was redefining authority—seeking a balance between tradition, sovereignty, and the pressures of a globalizing world.

When “Persia” Became “Iran”

In 1935, the government formally requested foreign states to use “Iran,” the name long used within the country itself (rooted in Īrān, “Land of the Aryans”). The timing reflected a national reorientation—asserting indigenous terminology within international diplomacy. Some historians also note the era’s fascination with ethnonational vocabularies, including Germany’s interest in Iran’s ancient Indo-European links; whatever the mix of motives, the shift affirmed an old identity in modern form.

A Continuing Legacy

From Achaemenid innovations in imperial governance to Sassanid cultural florescence, from the Safavid forging of a Shi‘i Iranian state to constitutional experiments under the Qajars, Iran’s story is one of endurance and reinvention. The modern nation carries forward millennia of statecraft, poetry, legal thought, urban design, and religious philosophy.

Ancient Persia did not vanish with Alexander; it reframed itself time and again—absorbing shocks, borrowing and lending ideas, and setting patterns other civilizations would emulate. To study Iran’s past is to watch the long arc of a civilization continually finding new forms for old strengths—an inheritance still visible in language, institutions, and the living culture of a society that has shaped, and continues to shape, the history of a wider world.