In Kandahar, Mullah Omar gathered roughly fifty followers—many of them young men who had studied religious teachings under him. These early members aimed to challenge the chaos spreading across Afghanistan. The word Taliban translates to “students,” a direct reflection of the group’s origins among young religious trainees who believed they could restore stability through strict governance.

Their rise was swift. As more Afghans grew disillusioned with the disorder of the civil war, the Taliban captured Kandahar and advanced toward the rest of the country. By 1996, they had taken Kabul and established control over most of Afghanistan, imposing a strict interpretation of Islamic law. Under their rule, television, music, and various forms of entertainment were forbidden. Girls’ education was banned, and women were required to wear full-body coverings known as burqas whenever they appeared in public.

During this period, the Taliban also provided protection to Osama bin Laden and members of Al Qaeda while they planned the September 11 attacks. This decision would ultimately lead to a major international intervention.

The U.S. Intervention and Taliban Retreat

When the Taliban rejected American demands to surrender Osama bin Laden after the September 11 attacks, the United States launched a military invasion to dismantle the group’s rule. The Taliban government collapsed rapidly under American airstrikes and ground operations carried out with support from Afghan allies.

Mullah Omar and senior Taliban leaders escaped across the border into Pakistan, where they regrouped and reorganised. From there, they began a lengthy insurgency that stretched across two decades. Despite being pushed from power, the Taliban steadily rebuilt their networks, launched coordinated attacks, and attempted to undermine the Afghan government’s authority.

In February 2020, the United States and the Taliban signed a landmark agreement outlining a phased American withdrawal over fourteen months. Although the deal was intended to create momentum for peace negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government, discussions progressed slowly and failed to produce a stable political settlement.

The Fall of Kabul and the Taliban’s Return

As international forces withdrew from Afghanistan, the Taliban launched a rapid and unexpected offensive across the country. City after city fell with minimal resistance, and by the time they reached Kabul, much of the Afghan military had either fled or surrendered. The President of Afghanistan left the country, and Taliban fighters entered the capital, reclaiming power after twenty years in exile.

Their return raised widespread global concern. Observers anticipated the reinstatement of harsh restrictions similar to those enforced during their previous regime. Many Afghans feared a revival of limitations on women’s rights, cultural expression, and personal freedoms.

The Taliban’s advance not only marked a dramatic shift in Afghanistan’s political landscape but also prompted the world to reconsider the future stability of the region. Understanding how the group re-emerged requires tracing their origins, ideology, and long-standing goals.

Who Exactly Are the Taliban?

The Taliban, whose name means “students,” form a militant Islamist movement that seeks to govern Afghanistan according to an uncompromising interpretation of religious law. Their ideological roots can be traced to the U.S.-backed mujahedeen fighters who resisted Soviet occupation during the 1970s and 1980s. Many early members were religious students influenced by strict teachings promoted in rural areas and border regions.

As Afghanistan descended into civil war during the 1990s, the Taliban gained strength, capturing territory from rival militias and government forces. By 1996, they had taken control of Kabul and established themselves as the country’s ruling force. Despite their rapid rise, not all of Afghanistan fell under their authority; pockets of resistance persisted, particularly in the northern regions.

Most international governments declined to recognise the Taliban as the legitimate rulers of Afghanistan due to their severe policies and human rights abuses. Their regime became infamous for violent punishments, institutionalised discrimination against women, suppression of free expression, and destruction of cultural heritage sites. Among their most notorious acts was the demolition of the centuries-old Buddhas of Bamiyan, an event that shocked the global community.

Their rule came to an end when U.S., Australian, and other Western forces invaded Afghanistan following the September 11 attacks. Nearly 3,000 people lost their lives in those attacks, prompting a global campaign to dismantle terrorist networks protected by the Taliban.

The Taliban’s Long Insurgency After 2001

Although foreign troops removed the Taliban from power relatively quickly, the movement did not disappear. Instead, it shifted from a ruling force to an insurgent network determined to drive out Western influence and eventually reclaim control. For twenty years, the Taliban conducted a relentless guerilla campaign against U.S. forces, their allies, and the Afghan national army.

Government-held cities remained under the administration of Kabul, but in the countryside—especially in the south and east—the Taliban retained significant influence. Many of their fighters drew support from Pashtun tribal regions where grievances against central authorities ran deep. Their ability to blend into rural communities, adapt to mountainous terrain, and avoid direct, large-scale confrontations gave them a long-term strategic advantage.

Despite being ousted, the Taliban remained united and motivated. They built shadow administrations in some regions, issued their own rulings, and taxed local communities. Slowly but steadily, they expanded their presence, waiting for a moment when international support for the Afghan government would wane.

A Leadership Hidden in Shadow

The founder of the movement, Mullah Mohammad Omar, disappeared from public view after the U.S. invasion. For years, his exact whereabouts remained unknown—even to many within the Taliban. Reports about his movements were vague, and his voice or appearance rarely surfaced in credible ways. It was only in 2015, two years after his actual death in 2013, that his son confirmed he had passed away.

Following his death, the group’s leadership experienced shifts but maintained continuity. The current supreme leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, oversees the movement’s religious and political direction. Under his guidance, the Taliban continued to expand their influence inside Afghanistan while negotiating with international actors outside the country.

Western military analysts note that estimates of the Taliban’s manpower vary widely. However, intelligence assessments indicate that a significant core force remained active throughout the two decades of conflict, supported by local networks and external sympathisers.

What the Taliban Seek: Their Vision and Rules

Under their first period of rule, Taliban laws drastically restricted nearly every aspect of daily life, especially for women. Women were forbidden from working, attending school, or even leaving home without a male family member as an escort. Those who appeared in public were required to be fully covered in a burqa, which concealed the entire body and face.

Music, television, and most forms of entertainment were outlawed. The Taliban established religious courts that handed down severe corporal punishments. These included public lashings, amputations for theft, and stoning for certain moral offences. Their rigid system left little room for dissent or cultural expression, and the consequences of disobedience were often brutal.

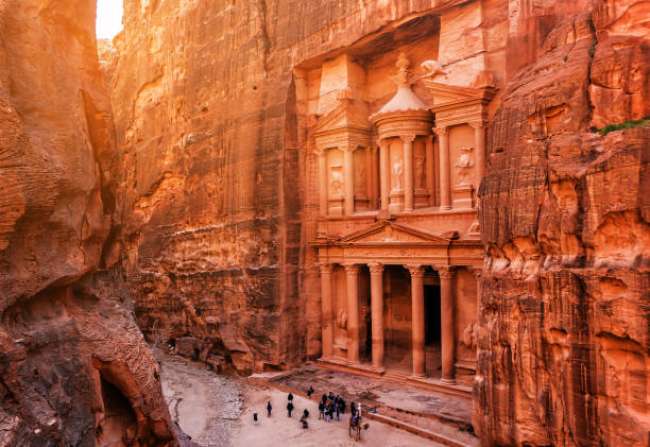

One of the most widely condemned acts of the regime was the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan—two monumental statues carved into the cliffs of central Afghanistan for over fifteen centuries. The Taliban viewed them as idolatrous and ordered their demolition, sparking global outrage.

Although the Taliban have repeatedly claimed they intend to govern differently today, many observers worry that the group’s promises conflict with reports coming from areas under their new rule. Some regions already show evidence of renewed restrictions on women’s employment and public visibility. In Kabul, for example, merchants have preemptively painted over images of women in shop windows, anticipating tighter controls on representation.

The Taliban’s Renewed Advance: How They Took Afghanistan Again

The question that many around the world asked in 2021 was: how did the Taliban regain control of Afghanistan so quickly after two decades of fighting? Their advances were not the result of a single factor but rather a combination of strategy, timing, and psychological leverage.

As foreign forces began their final withdrawal in May, both the American and Afghan governments remained publicly confident that the Afghan military—numbering more than 300,000 and equipped with sophisticated U.S.-supplied hardware—would resist effectively. On paper, the Afghan forces appeared strong and capable. In practice, however, long-standing internal problems had eaten away at their ability to fight.

Corruption weakened command structures. Leadership was inconsistent, and recruitment within the army had been unstable for years. Desertion was common as soldiers often went months without pay or proper support. U.S. government inspectors had repeatedly warned that the Afghan national forces were unsustainable without constant foreign backing.

Why the Afghan Army Collapsed

Although Afghan soldiers fought fiercely in several places—particularly in the southern city of Lashkar Gah—the overall military struggled without continuous American airpower and logistical support. With the departure of Western forces, many units suddenly found themselves isolated, poorly supplied, and deeply uncertain about the future.

The Taliban, meanwhile, demonstrated cohesion and determination. Their fighters were motivated by a clear objective: retaking the country. As pressure mounted, entire Afghan units surrendered or fled. Many soldiers, unsure of whether help would arrive, decided survival was preferable to a hopeless battle.

In some regions, troops abandoned their posts and crossed borders into neighbouring countries. Their withdrawal created gaps the Taliban quickly filled, accelerating the group’s momentum.

The Role of Morale and Psychological Pressure

The collapse of the Afghan military was not only a battlefield defeat—it was also the product of years of declining morale. The turning point began when the United States signed a withdrawal agreement with the Taliban, signalling that international support for Afghanistan’s government had a clear end date. For many Afghans who relied on Western protection and aid, the deal felt like a warning that they would soon face the Taliban on their own.

As the withdrawal timetable progressed, the Taliban stepped up both military attacks and targeted assassinations. Journalists, activists, and local officials became frequent victims of killings meant to spread fear. This created an atmosphere of inevitability: the perception that the Taliban were destined to win and that resistance would only prolong suffering.

Taliban propagandists circulated messages claiming victory was certain. Soldiers and civil servants in some areas received text messages urging them to abandon their posts to avoid harm. Community elders were used as intermediaries to pressure garrisons into surrender. The promise of safe passage—or threats of harsher consequences—encouraged many officials to negotiate instead of fight.

By the time the Taliban reached several major cities, the psychological groundwork had already been laid. Many local leaders concluded that resistance was pointless, and cities fell with remarkable speed.

The Collapse of Warlords and Regional Militias

Afghanistan has a long history of powerful warlords who controlled territories with their own militias. In earlier eras, these leaders stood as formidable opponents to Taliban expansion. Yet during the 2021 offensive, their forces were unable to counter the insurgents.

As confidence in the central government faded, the authority of these warlords weakened dramatically. Prominent figures like Ismail Khan in Herat were captured during the Taliban’s advance, stripped of the regional influence they had once wielded. In the northern regions, leaders such as Abdul Rashid Dostum and Atta Mohammad Noor, who had commanded large militias for decades, were forced to flee to Uzbekistan as their fighters abandoned vehicles, equipment, and uniforms in a chaotic retreat from Mazar-i-Sharif.

The swift dissolution of these militia networks revealed just how deeply the sense of abandonment had spread throughout the country. Once the perception of certain Taliban victory took hold, the resistance that many expected from long-standing warlords simply evaporated.

How the Taliban Achieved Their Rapid Victory

Long before launching their final offensive in May, the Taliban had been quietly negotiating deals at multiple levels of Afghan society. These agreements ranged from local ceasefires to direct arrangements with provincial leaders. The logic was simple: if defeat seemed inevitable, why fight?

This strategy proved extraordinarily effective. When the Taliban captured their first provincial capital, the momentum became unstoppable. Each new surrender reinforced the belief that more cities would fall, accelerating the collapse. Within less than two weeks, they controlled the entire country. The images circulating during their final march toward Kabul did not show large-scale battles. Instead, many photographs showed Taliban representatives seated beside government officials, calmly discussing the terms of surrender.

U.S. intelligence estimates had predicted that the Afghan government might fall in approximately ninety days after the Taliban seized their first major city. Yet the speed of the collapse exceeded even those warnings. The fall of Kabul came in a fraction of that time, completing the Taliban’s return to power after two decades of insurgency.

Reflection on Afghanistan’s Turbulent Transition

The Taliban’s resurgence represents one of the most dramatic political reversals of the 21st century. Their ability to return to power after being removed by an international coalition for twenty years reflects a complex mix of military endurance, strategic patience, and the profound weaknesses within Afghanistan’s political structures.

The events surrounding their takeover highlight several longstanding issues: reliance on foreign support, deep-rooted corruption, fragmented leadership, and a failure to build institutions capable of withstanding internal and external pressure. At the same time, the Taliban’s rapid advance illustrates how psychological influence, local negotiations, and a consistent narrative of victory can outweigh conventional military strength.

Afghanistan now faces an uncertain future as the new leadership seeks to consolidate power. How they choose to govern—and whether they keep their promises regarding social and civil rights—will determine the country’s path in the years to come. The world continues to watch closely, aware that the stakes are high not only for Afghanistan’s people but for regional stability as a whole.

Additional Shifts in Afghanistan After 2021

Economic Adjustments and Everyday Survival

Since the Taliban regained control, Afghanistan’s economy has gone through a profound transformation that has shaped daily life for ordinary citizens. With international funding suspended, government salaries shrank or disappeared entirely, pushing many families into poverty. Rural communities that once depended on foreign aid now rely on barter systems, informal loans, or seasonal labour just to provide basic necessities. Markets remain active, but most households have drastically reduced their spending.

Despite hardship, certain sectors have seen limited activity. Trade with neighbouring countries such as Pakistan, Iran and Uzbekistan has continued, particularly in agriculture, construction materials, coal, and small manufactured goods. However, these exchanges occur under tight restrictions and generate insufficient revenue to compensate for the loss of international aid that once supported hospitals, schools, infrastructure and civil services.

Widespread unemployment has forced many Afghans to leave the country in search of work. Remittances from abroad now play an increasingly important role in helping families survive, though restrictive banking conditions make sending money home more complicated than before.

Restrictions on Education and Knowledge Access

One of the most defining consequences of the Taliban’s rule has been a sweeping limitation on education, especially for girls and young women. By 2023, secondary schools for girls were essentially shut down nationwide, followed by bans on university attendance for women. Many female students tried enrolling in online courses or informal community-based classes, but internet restrictions and public crackdowns made long-term participation difficult.

Some regions developed underground learning initiatives where volunteer teachers and students privately organised lessons, often at personal risk. In rural districts, even boys’ schooling has become inconsistent due to teacher shortages, lack of equipment, and political pressure to replace modern curricula with more religious instruction. This decline in education may shape the country’s trajectory for decades, as a generation grows up with fewer academic and professional opportunities.

Shifts in Social Norms and Daily Life

Life in Afghanistan has changed significantly under renewed Taliban authority. Dress codes, public behaviour, and social gatherings are monitored closely, especially in cities. Music has been restricted once again, and many entertainment venues have shut down or changed their operations to comply with Taliban expectations.

Women face barriers in nearly every sphere of public life. Most professional roles—including government positions, banking, education, and media—became inaccessible to them. Some women have managed to continue working from home or in discreet private networks, but many lost their livelihoods entirely. In several provinces, local commanders interpret rules differently, leading to inconsistency from one district to another. This uneven enforcement creates confusion but also, in rare cases, small pockets of flexibility.

Media, Communication and Information Control

After retaking power, the Taliban placed heavy restrictions on independent media outlets. Many journalists fled, while others face pressure to avoid criticism of the authorities. By 2025, internet access became increasingly regulated. The nationwide fibre-optic blackout ordered by the Taliban led to severe disruptions in business, education, communication and humanitarian coordination.

Social media use is monitored, and posting content viewed as critical of the authorities carries risks. Despite this, Afghans continue to use online platforms cautiously to share news, organise community assistance and report abuses.

Security Conditions and Internal Conflicts

While the Taliban claim they have brought stability to the country, security threats remain. The Islamic State – Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) increased its attacks on civilian areas, religious minorities, and Taliban installations. Their rivalry with the Taliban has introduced another layer of violence that affects multiple provinces.

Additionally, armed resistance groups have attempted to challenge Taliban control in mountainous regions, although these movements remain fragmented. Border tensions with neighbouring countries periodically erupt, especially along the frontier with Pakistan due to disputes over cross-border militancy and territorial demarcation.

International Engagement and Negotiations

With no formal recognition from most Western countries or the United Nations, the Taliban government faces obstacles in participating in global forums. Still, regional diplomacy has evolved gradually. Russia’s decision in 2025 to remove the Taliban from its list of banned organisations opened the door to new conversations about economic cooperation and security coordination.

China has maintained a pragmatic relationship with the Taliban, especially concerning mining projects and counterterrorism assurances. Pakistan continues to be a key player in Afghan politics, although relations are not without tension. Iran, too, interacts with the Taliban on matters related to border security and water rights.

Despite these contacts, Afghanistan remains isolated economically and politically, limiting its ability to receive development funding or attract major long-term investment.

Humanitarian Needs and Aid Challenges

Nearly half of Afghanistan’s population requires some form of humanitarian assistance. Aid organisations operate under difficult conditions, facing restrictions on female staff, unpredictable approval processes and logistical disruptions caused by conflict or weather. The collapse of public services—especially in health care—forced international organisations to take on essential responsibilities.

However, global fatigue and shifting priorities have reduced the amount of aid available. Many agencies warn that without more consistent cooperation from the authorities and increased funding, future crises could worsen.