Mecca stands as the beating heart of the Islamic world, revered for over fourteen centuries as the holiest city in Islam. It is the birthplace of Prophet Muhammad and the site where Muslims believe the angel Gabriel revealed the words of the Quran to him — revelations that became the foundation of one of the world’s largest faiths. Since that moment in the 7th century, Mecca has remained the most important religious center for Muslims everywhere, and every year millions journey to its sacred grounds to perform the Hajj pilgrimage, one of Islam’s five essential pillars.

For Muslims, Mecca is far more than a physical city — it’s a symbol of divine unity and the place toward which believers all over the globe turn their faces five times a day in prayer. It embodies centuries of devotion, history, and shared faith, linking the present to the earliest roots of Islamic revelation. Out of respect for its sacred status, only Muslims are permitted to enter Mecca today.

The Geography and Setting of Mecca

Located in the western region of Saudi Arabia, in an area known as the Hejaz, Mecca lies inland from the Red Sea coast. The nearest coastal city, Jeddah, serves as its main port and gateway for pilgrims arriving by air or sea. The capital of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh, is found approximately 550 miles to the northeast, while Medina — the second most significant city in Islam due to the Prophet Muhammad’s migration there — lies around 280 miles north of Mecca.

The city sits in a narrow valley surrounded by the vast expanse of the Arabian Desert, creating a landscape that is both stark and spiritually awe-inspiring. The surrounding mountains frame the city like natural walls, emphasizing its seclusion and sanctity. The climate is extremely hot and arid, yet for centuries people have lived and traded here, drawn by its location on ancient caravan routes and, later, by its spiritual importance.

Saudi Arabia itself borders Yemen and Oman to the south, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Bahrain to the east, and Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait to the north. Despite being set amid harsh desert conditions, Mecca thrives as a symbol of endurance and divine connection — a place where faith has literally reshaped the land.

Mecca, known in Arabic as Makkah and historically as Bakkah, lies within the rugged Sirat Mountains, not far from the Red Sea. It is universally recognized as the holiest of Muslim cities. Prophet Muhammad was born here, and it is toward this sacred center that all Muslims face in daily prayer. The city’s sanctity is so deeply rooted that all devout Muslims who are physically and financially able strive to visit Mecca at least once in their lifetime to perform the Hajj. Because of its sacredness, the city’s boundaries remain closed to non-Muslims.

Ancient History and the Birth of Islam

Before Islam’s emergence, Mecca was already an established center of trade and religious activity in the Arabian Peninsula. Yet the details of its earliest history remain largely mysterious, woven together through fragments of oral traditions and ancient accounts. What is clear is that pre-Islamic Mecca was inhabited by various tribes, including the Quraysh, Bedouin, and other semi-nomadic peoples who engaged in trade across the desert.

The city’s economy revolved around its strategic position on caravan routes that linked southern Arabia, Syria, and the broader Middle East. Along with goods like spices, incense, and textiles, Mecca was also a crossroads for ideas and beliefs. While many local tribes practiced polytheism and animism, followers of monotheistic faiths — Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians — passed through as well, leaving traces of their traditions in the region’s cultural fabric.

The Kaaba, a cubic stone structure located in the center of Mecca’s Grand Mosque, was already revered before the birth of Islam. It is believed that the Black Stone, set into one of its corners, was venerated by early tribes long before Muhammad’s time. Muslims hold that the Black Stone descended from heaven as a sign to Adam and Eve, marking the spot where they were to build the first temple to God. Though the object’s original purpose in pre-Islamic worship remains uncertain, its continuity into Islamic ritual underscores Mecca’s long spiritual heritage.

Muhammad himself was born in Mecca around 570 CE, into the Quraysh tribe — respected but not among the wealthiest of families. His father died before his birth, and his mother passed away while he was still young. Raised by his grandfather and later his uncle, Muhammad grew up familiar with the struggles and inequalities of his society. As a young man, he worked for Khadijah, a successful widow and merchant. His reliability and honesty soon led to their marriage — a partnership of affection and respect that deeply influenced his later life.

During his early years, Muhammad was aware of various religious beliefs that surrounded him. Influences from Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism were present in the region, introducing him to ideas of divine revelation and monotheism. According to Islamic tradition, during one of his annual retreats for meditation and prayer in a cave near Mecca, the angel Gabriel appeared before him and revealed the first verses of what would become the Quran. Initially shocked and fearful, Muhammad gradually came to accept his prophetic mission — to proclaim the message of the one true God, Allah.

Hajj: The Great Pilgrimage of Islam

Each year, millions of Muslims from every corner of the globe converge upon Mecca to perform the Hajj — a spiritual journey that has been undertaken for over a thousand years. The Hajj is both a deeply personal act of devotion and one of the most profound collective expressions of faith in the world. It is a physical, emotional, and spiritual test, carried out over five days, meant to renew the soul, unite believers, and honor the legacy of Abraham.

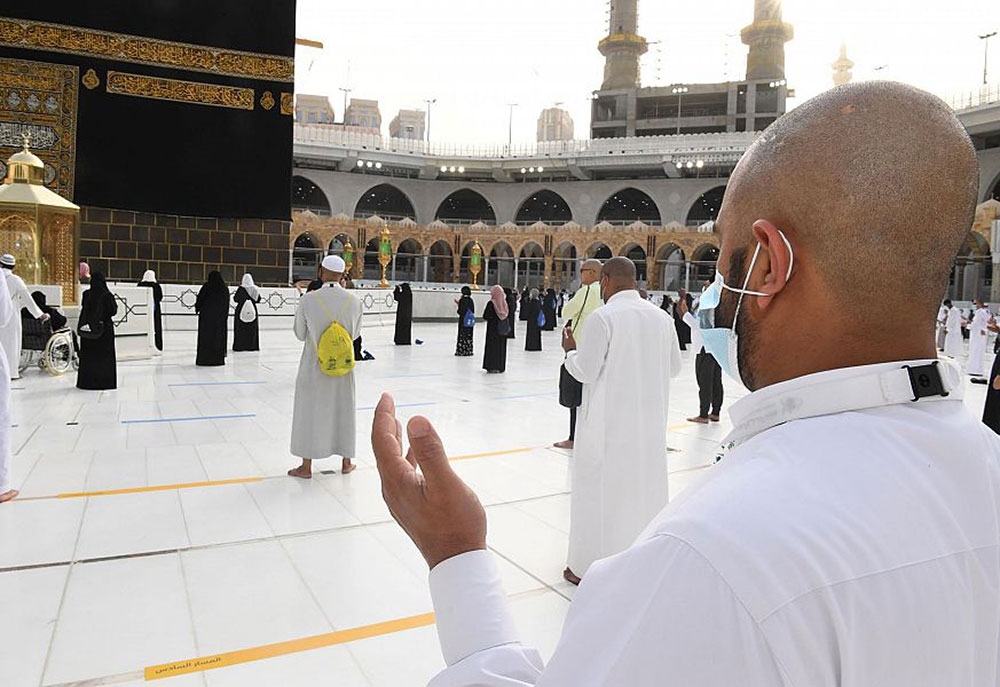

At any given moment during Hajj season, up to two million pilgrims can be found within the city. The experience is both majestic and humbling: an ocean of white-clad worshippers moving together around the Kaaba, their voices rising in unified prayer. The sight represents not only equality before God but also the unity of humanity under a shared faith.

The logistics are staggering — Mecca becomes a city that never sleeps, alive with the movement of pilgrims, volunteers, and officials managing transportation, sanitation, food, and health care for millions. Yet behind the crowds and the organization lies the essence of the pilgrimage: the surrender of worldly distinctions and the pursuit of spiritual purification.

What the Hajj Means in Practice

The word Hajj in Arabic means “to set out for a journey” or “pilgrimage.” It is one of the Five Pillars of Islam, alongside the declaration of faith, daily prayer, fasting during Ramadan, and charitable giving. Every able-bodied Muslim with the financial means is expected to perform the Hajj at least once in their lifetime.

This sacred journey takes place only once a year, during the twelfth month of the Islamic lunar calendar — Dhul-Hijjah. Because the Islamic year is shorter than the Gregorian one by about eleven days, the timing of the Hajj shifts slightly each year. For five consecutive days, pilgrims perform a carefully prescribed series of rituals that commemorate acts of faith, sacrifice, and devotion tracing back thousands of years.

Among these rituals are moments of reflection, prayer, and symbolic re-enactment of sacred events. The culmination of the pilgrimage coincides with Eid al-Adha, the Festival of Sacrifice, celebrated not only by those in Mecca but by Muslims worldwide. This festival honors Prophet Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son at God’s command, an act of ultimate obedience and faith.

Completing the Hajj carries lifelong spiritual significance. Pilgrims return home with the honorary title of “Hajji,” symbolizing their fulfillment of one of Islam’s greatest obligations. More than that, they carry back an inner transformation — a renewed sense of humility, purpose, and unity with their faith community.

The Spiritual and Historical Foundations of the Hajj

While the Prophet Muhammad formalized the rituals of the Hajj, its roots stretch back to Abraham (Ibrahim), a figure revered across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The pilgrimage honors his unwavering faith and his family’s struggles in the ancient valley of Mecca.

According to Islamic tradition, God commanded Abraham to leave his wife Hagar and their infant son Ismail (Ishmael) in the barren desert between the two hills of Safa and Marwah. When their water ran out, Hagar ran desperately back and forth seven times between the hills searching for sustenance. In her anguish, a miraculous spring — the Zamzam Well — burst forth from the ground, saving both mother and child.

Abraham later returned to rebuild the Kaaba with Ismail, marking it as a place of worship dedicated to the one true God. In time, this site became the focal point for monotheistic devotion in Arabia. Muslims believe that God then commanded Abraham to call humanity to pilgrimage — a divine invitation that echoes through the ages as the foundation of the Hajj.

The Kaaba – The Center of the Islamic World

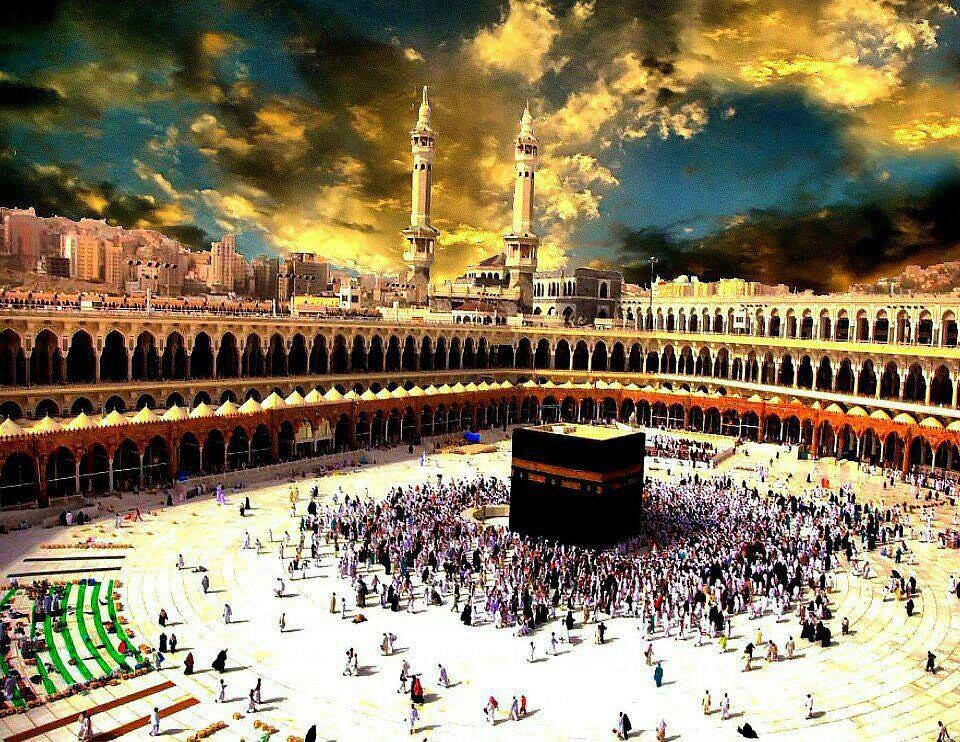

At the heart of Mecca stands the Kaaba, a rectangular stone structure draped in black silk embroidered with Quranic verses in gold thread. Every Muslim prayer, no matter where in the world it is performed, is directed toward this single point. The Kaaba itself is not worshipped; it serves as a unifying symbol of faith, orienting hearts and minds toward God.

The Kaaba’s story is deeply interwoven with humanity’s oldest spiritual narratives. Islamic tradition teaches that even before humanity existed, angels worshipped God on that sacred ground. Later, Adam is said to have built the first sanctuary there, which was eventually destroyed by time. When Abraham came centuries later, he and his son Ismail rebuilt the structure on its ancient foundations, restoring its purpose as a house of monotheistic worship.

Architecturally, the Kaaba is simple — four stone walls forming a cuboid shape rather than a perfect cube, with its corners roughly aligned to the cardinal directions. Inside, there are no idols or ornate decorations, only white marble walls, three wooden pillars, and a small staircase leading to the roof. The simplicity reflects the essence of Islam itself: purity, humility, and unity.

Each year, the Kaaba is covered with a new black cloth called the Kiswah, replaced during the pilgrimage in a ceremonial act of reverence. In one corner is the Black Stone, believed to have been given to Abraham by the angel Gabriel. Pilgrims often attempt to kiss or touch it during their circumambulation, though most simply point toward it in devotion.

According to Islamic legend, the Black Stone once shone bright white but turned dark from absorbing the sins of countless believers who touched it seeking forgiveness.

Another significant relic, the Station of Abraham, lies nearby — a stone said to bear the footprints of Abraham himself as he oversaw the building of the Kaaba. Enclosed today within an ornate golden structure, it remains one of the most venerated spots within the Grand Mosque.

Prophet Muhammad and the Purification of the Kaaba

Centuries after Abraham, Mecca’s sacred shrine had fallen into idolatry. The Kaaba, originally built for monotheistic worship, had become filled with idols representing numerous tribal gods. The Quraysh tribe, which managed the shrine, profited greatly from these pagan pilgrimages.

When Prophet Muhammad began receiving revelations around the age of forty, his message of pure monotheism challenged the religious and economic order of Mecca. The Quraysh, threatened by the loss of influence and wealth, persecuted him and his followers, forcing them into exile in Medina.

A decade later, Muhammad returned to Mecca at the head of a unified Muslim community. Upon reclaiming the city, he entered the Kaaba and destroyed all idols within, restoring it once again as a sanctuary devoted solely to the worship of Allah. This act marked a turning point in Islamic history — the transformation of Mecca into the spiritual center of a global faith.

Today, the Kaaba remains closed to pilgrims during the height of the Hajj because of the immense crowds, but at other times of the year, select visitors may be allowed inside. Those who do describe it as profoundly peaceful — a space of quiet reverence, where simplicity mirrors the humility of the believer before God.

Rituals of the Hajj

The Hajj is defined by a sequence of sacred rituals, each rich with symbolic meaning. The most iconic among them is Tawaf, the circumambulation of the Kaaba. Pilgrims walk counterclockwise around it seven times, their motion representing the unity of believers moving together in harmony around the center of their faith. The number seven has deep spiritual resonance — associated with divine perfection and reflected in many religious traditions.

Other rituals include the Stoning of the Devil (Ramy al-Jamarat), where pilgrims throw pebbles at three stone pillars in the city of Mina. This act reenacts Abraham’s rejection of temptation when Satan tried to dissuade him from obeying God.

Afterward comes the sacrifice of an animal, usually a sheep or goat, symbolizing Abraham’s obedience and the mercy shown by God when He replaced his son with a ram. The meat from these sacrifices is distributed to the poor, reinforcing Islam’s message of charity and equality.

Another important rite is the Sa’ee, which commemorates Hagar’s desperate search for water for her son Ismail. Pilgrims walk back and forth seven times between the hills of Safa and Marwah within the Grand Mosque complex. The area is now enclosed in an air-conditioned marble gallery, but its meaning remains profound — a reminder of human endurance, faith, and divine compassion.

The pilgrimage reaches its spiritual climax on the Plain of Arafat, where millions gather in silent worship and prayer. It was here that Prophet Muhammad delivered his final sermon, calling for justice, equality, and compassion among all people. Pilgrims spend the day in contemplation, seeking forgiveness and renewal before sunset.

Restrictions and Access — Who May Perform Hajj

Participation in the Hajj is reserved exclusively for Muslims. The Saudi Arabian government enforces this rule with extreme strictness — non-Muslims are not permitted to enter the holy city of Mecca under any circumstances.

This regulation has existed for centuries, rooted in the desire to preserve the sanctity of the sacred space. Non-Muslims attempting to enter face immediate deportation and potential lifetime bans. While there have been rare instances in history of outsiders disguising themselves to witness the pilgrimage, such occurrences are extraordinarily uncommon.

To ensure security and authenticity, entry for pilgrims is highly regulated. Those wishing to perform the Hajj must obtain a special visa issued by the Saudi Ministry of Hajj through authorized travel agencies. Applicants are required to provide personal identification, vaccination records, and in some cases, certification from an imam affirming that they are practicing Muslims.

For converts to Islam living in Western countries, documentation from their mosque confirming their conversion is also mandatory. The process is meticulous and lengthy — ensuring that those who embark on the journey do so in true faith and spiritual readiness.

Women and Children During Hajj

Women and children also play an important part in this pilgrimage, though there are distinct regulations. Parents may bring their young children to experience the journey, but a child’s participation does not fulfill their personal obligation, which must be completed independently once they reach maturity.

For women, the rules are specific: all Muslim women physically and financially able to perform Hajj are required to do so, yet under certain conditions. Traditionally, women under the age of 45 must be accompanied by a male guardian, known as a mahram — such as a husband, father, brother, or adult son. Women over 45 may travel without a guardian if they are part of an organized group and provide a notarized letter of consent from their male relative.

Women belonging to the Shia branch of Islam are often allowed to attend Hajj without a mahram, reflecting differences in religious interpretation. The essence of the rule, however, is rooted in ensuring safety and protection during travel.

Regarding attire, women cover their hair with a scarf but may not wear a face veil (niqab) or full-body covering (burqa) during Hajj. This rule originates directly from the Prophet Muhammad’s instruction that women in a state of pilgrimage purity should not cover their faces or hands. To maintain modesty, many women opt for alternative coverings like wide sunglasses or medical masks, though these are based on personal choice.

Men wear a distinct outfit called the Ihram — two unstitched white cloths, one wrapped around the waist and another over the shoulders. This attire erases visible distinctions of wealth and status, emphasizing equality before God. When millions stand together in identical garments, the symbolism is unmistakable: no one is greater than another in the eyes of the Divine.

Managing the Pilgrimage — Logistics and Scale

The organization behind Hajj is a logistical marvel, requiring vast resources, coordination, and infrastructure. Every year, the Saudi government invests billions of dollars to accommodate millions of pilgrims safely and efficiently.

Each year’s Hajj sees around two million attendees from over a hundred nations — far more than any other recurring event on Earth. To manage such enormous numbers, Saudi Arabia imposes strict quotas on each country’s pilgrim count and operates an immense network of facilities dedicated solely to the pilgrimage season.

Roads, air routes, and shuttle systems are designed to handle mass movement, with certain areas restricted entirely to pedestrian travel. Personal vehicles are banned during Hajj to reduce congestion and prevent chaos. Multi-level bridges, air-conditioned tunnels, and wide open courtyards enable pilgrims to circulate freely around the Grand Mosque and nearby holy sites.

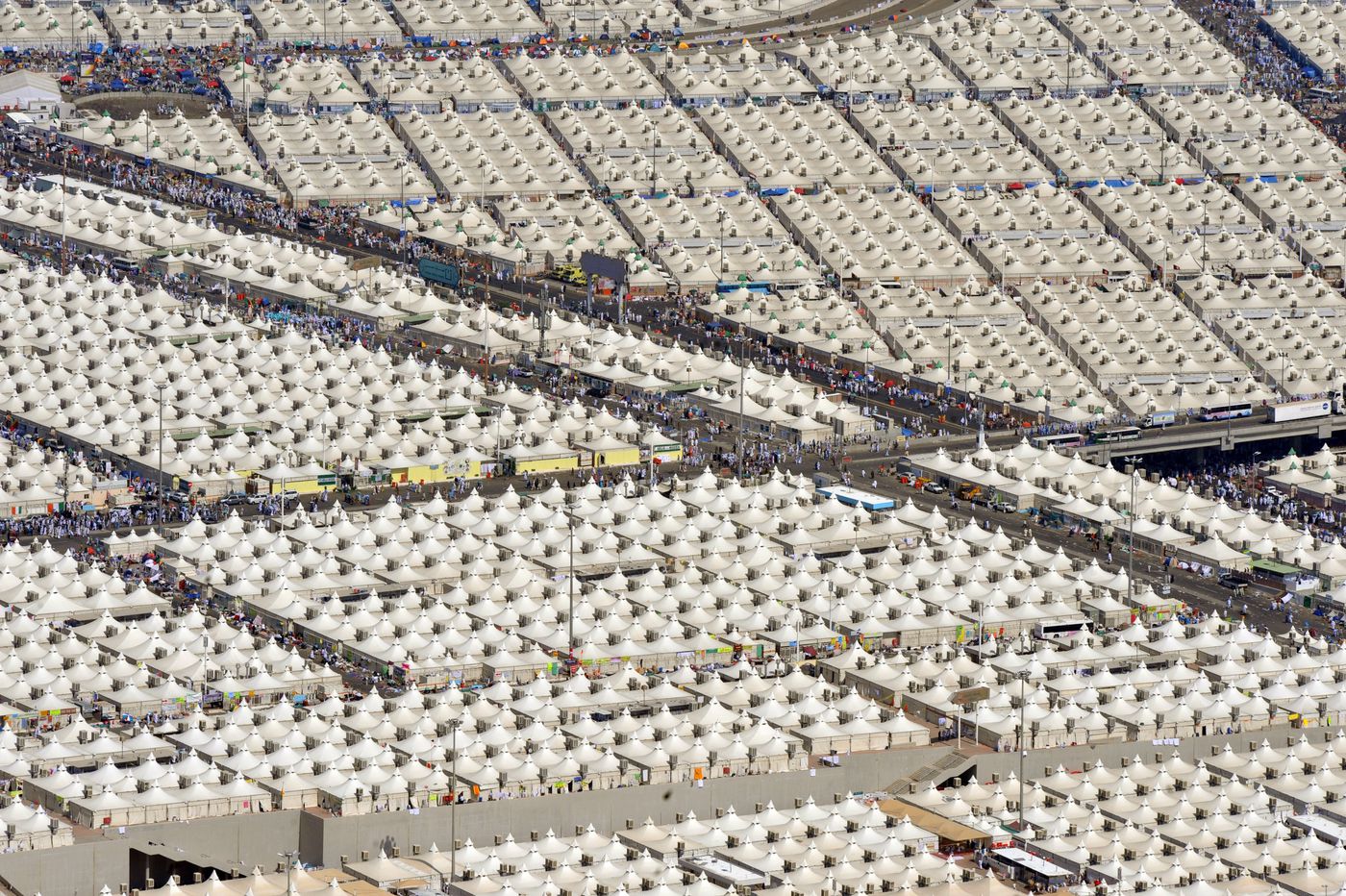

The tent city of Mina, located a few kilometers east of Mecca, is one of the most striking examples of human planning for faith. Here, more than 160,000 white, fireproof, air-conditioned tents stretch across the valley — forming temporary accommodation for the pilgrims. Men and women are housed separately, with each tent typically hosting around fifty people.

While most accommodations are simple and communal, luxury tents with private services, sometimes costing up to $10,000 per person, do exist. However, authorities have discouraged such practices, arguing that they contradict the pilgrimage’s spirit of humility and equality.

For fifty-one weeks each year, Mina lies silent — a ghost city in the desert. Yet during Hajj, it transforms into a living metropolis filled with prayers, chants, and unity.

Health, Safety, and Challenges

Hosting millions of pilgrims poses immense health and safety challenges. Overcrowding, extreme temperatures, and the diversity of attendees heighten the risk of disease outbreaks, dehydration, and stampedes.

To prevent health crises, Saudi Arabia enforces strict vaccination requirements, particularly for diseases like meningitis and yellow fever. Pilgrims are urged to stay hydrated and shield themselves from the desert sun. During Hajj, thousands of water distribution points and misting systems help reduce heat stress, while emergency teams remain on standby day and night.

Despite modern systems, tragedies have occurred in the past. Stampedes in 1990, 1994, 2003, and 2015 led to thousands of deaths, prompting significant safety reforms. New pedestrian routes, timed movements, and crowd-monitoring technology have since been introduced.

Medical facilities are an essential part of this infrastructure. In and around Mecca, temporary hospitals and clinics are equipped with thousands of beds and staffed by tens of thousands of medical professionals. Healthcare is provided free of charge to all pilgrims, regardless of nationality.

The Saudi government continuously improves emergency preparedness, adding surveillance drones, digital wristbands for tracking, and even AI-based crowd analytics to enhance safety and flow management.

The Political and Religious Dimensions of Hajj

The Hajj also plays a central role in global Islamic politics. Saudi Arabia’s identity as the “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques” — Mecca’s Masjid al-Haram and Medina’s Prophet’s Mosque — grants it immense religious authority across the Muslim world.

However, this responsibility has at times led to tension, particularly with Iran. Disputes between the Sunni Saudi government and Shia-led Iran have occasionally turned political disagreements into religious ones. Both nations claim to protect the faith’s integrity, but their rivalry has at times overshadowed the unity that the pilgrimage is meant to represent.

Incidents like the 2015 stampede fueled accusations and counteraccusations, with Iranian leaders blaming Saudi mismanagement and Saudi officials rejecting those claims. In some years, Iranian citizens were even barred from attending the Hajj — a rare political rupture in an event that transcends national borders.

Yet, in spite of these disputes, the Hajj remains an enduring symbol of peace and equality. Each year, millions of Sunnis and Shias, Arabs and non-Arabs, men and women, young and old, gather shoulder to shoulder in worship — united by faith, not divided by politics.

The Universal Message of the Hajj

The Hajj stands as one of humanity’s most powerful expressions of unity. Every pilgrim leaves behind comfort, status, and worldly distinction to stand as an equal before God. The journey demands physical endurance, patience, humility, and devotion, but it offers spiritual cleansing and a renewed sense of purpose.

In its essence, the Hajj teaches compassion, tolerance, and solidarity. It reminds Muslims — and indeed all people — that faith transcends race, nationality, and wealth. The sight of millions of pilgrims circling the Kaaba together in a single rhythm of prayer captures what it means to be part of something greater than oneself.

For Muslims, completing the Hajj is not an end but a beginning — a rebirth into a purer state of faith and consciousness. And for the world, it remains one of the most moving demonstrations of devotion, discipline, and shared humanity ever witnessed.