Petra is an ancient city carved into the rose-colored cliffs of what is now southern Jordan, dating back to around the 4th century B.C. Once a thriving metropolis and an essential trading hub of the Nabataean Kingdom, its remnants today tell stories of craftsmanship, devotion, and survival amid harsh desert landscapes. The sprawling ruins now serve as both a vital archaeological site and one of the world’s most remarkable travel destinations.

This visual and descriptive journey through Petra offers a sense of its wonder—the scale of the cliffs, the precision of its rock-cut temples, and the silent grandeur of its valleys. Every pathway, gorge, and ridge reveals how a civilization without modern tools carved an entire world from stone and engineered water systems that kept their city alive in the middle of an unforgiving desert.

Petra lies roughly 150 miles south of both Jerusalem and Amman—the capital of Jordan—and sits almost halfway between Damascus in Syria and the Red Sea. This made it a perfect location for trade routes that connected Arabia, Egypt, and the Mediterranean. Camel caravans once passed through here carrying incense, silk, and spices, filling the narrow gorges with life and commerce.

What makes Petra unique in the eyes of archaeologists and historians is not only its remarkable facades but also the Nabataeans’ advanced understanding of water engineering. Through a series of carved channels, cisterns, and dams, they transformed a barren landscape into a sustainable home. Combined with its dramatic sandstone architecture and natural beauty, Petra earned the nickname “The Rose City”—a reference to the warm pink hues that glow across its walls at sunrise and sunset.

Recognizing its cultural and historical importance, UNESCO designated Petra a World Heritage Site in 1985. Since then, it has also been listed among the New Seven Wonders of the World, attracting millions of visitors who come to witness its breathtaking harmony between human art and nature’s geology.

The journey into Petra begins through Bab as-Siq, the “Gateway to the Siq.” This narrow entrance opens the passage to the heart of the ancient city. Right at the start, visitors encounter the enigmatic Block Tombs, their simple, squared shapes carved directly into stone. Nearby lies the Aslah Triclinium, home to one of the oldest dated inscriptions in Petra. Although easily reached, few travelers stop here, making it a quiet corner to imagine how priests and nobles once gathered in its shaded halls for rituals and feasts honoring the dead.

The early path hints at Petra’s unique charm: the sense of discovery that builds with every step. Each turn reveals carved surfaces that shift in tone with the sunlight, whispering of centuries of devotion and artistry.

Not far beyond, the Obelisk Tomb and Bab as-Siq Triclinium stand side by side—two entirely different monuments carved around the same time, between 40 and 70 A.D. Despite their contrasting designs, both were functionally connected, possibly used for ceremonial burials. The Obelisk Tomb features tall, pointed obelisks sculpted directly from the sandstone, likely representing the souls of the deceased or gods watching over them. Below, the Triclinium’s open chamber once echoed with chants and incense during funerary feasts.

In front of these monuments, pit graves still mark the rock surface—humble reminders of Petra’s deeply spiritual culture that valued the afterlife as much as daily trade. The blending of Egyptian, Hellenistic, and local Nabataean motifs makes this site an early example of Petra’s cultural fusion.

The Siq, Petra’s most iconic pathway, is a winding sandstone corridor stretching for about 1.2 kilometers. This natural fissure, only about 3 meters wide in places and nearly 70 meters deep, serves as a dramatic prelude to the city’s main treasures. The Siq twists and narrows, its walls glowing in shades of orange, pink, and violet depending on the hour.

Running along both sides of this passage are the remains of the Nabataean water channels—ingenious systems that once carried fresh water from distant springs into the heart of Petra. These carved conduits and clay pipes reveal how advanced the Nabataeans were at controlling and preserving water in such a dry environment. As you walk through the Siq, the faint murmur of wind against rock seems almost like the echo of that ancient flow.

Halfway through the Siq lies the Sabinos Alexandros Station, where rows of votive niches appear in the stone walls. Some still bear inscriptions, others display the faint outlines of small altars and symbolic reliefs. These niches, known as betyls, represent sacred stones associated with Nabataean gods and goddesses. Worshippers once paused here to offer incense or prayers as they entered the holy city.

This stretch of the Siq tells as much about religion as it does about art. Each carved surface carries the handprint of a culture that blended spirituality and stonework so seamlessly that even its pathways became sanctuaries. The play of shadow and light across these walls adds a mysterious rhythm—as if every ray of sun was designed to illuminate the divine.

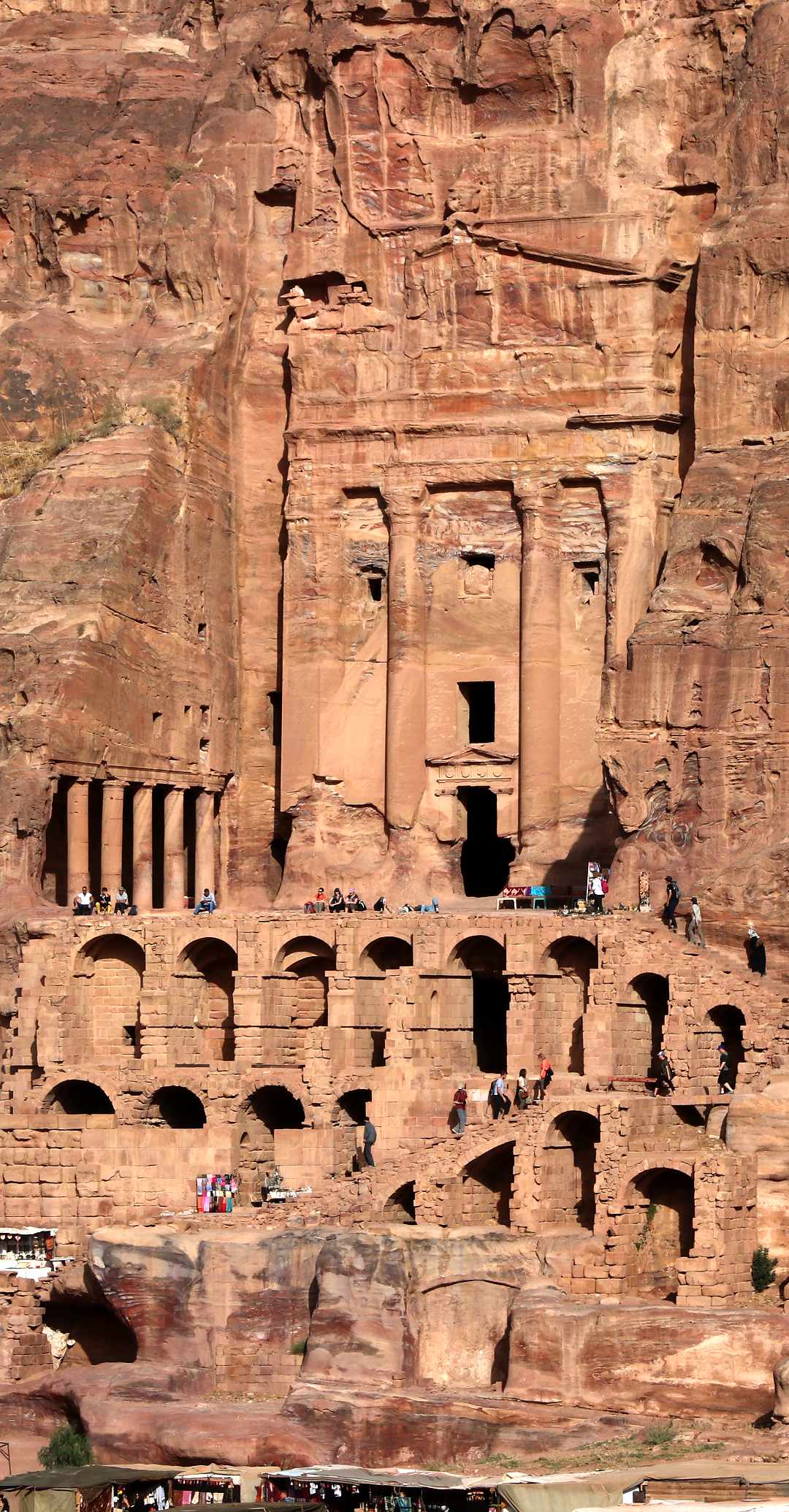

Emerging from the narrow gorge, travelers are suddenly met by the breathtaking sight of Al-Khazneh, or the Pharaoh’s Treasury—Petra’s most famous and photographed monument. According to Bedouin legend, a fleeing Egyptian pharaoh hid his treasure inside the urn that crowns the facade. The name “Khazneh al-Fira’un”—meaning “Pharaoh’s Treasury”—has stuck ever since.

At first sight, it’s hard to believe that this 40-meter-high masterpiece was carved entirely from living rock nearly two thousand years ago. The contrast between the confined Siq and the Treasury’s sudden grandeur leaves every visitor momentarily speechless—a cinematic reveal unlike any other archaeological site on Earth.

The facade of Al-Khazneh, about 25 meters wide and 39 meters high, dates from the early Roman period—probably the 3rd or 4th decade of the first century A.D. Every column, frieze, and sculpture was meticulously hewn by hand. The central figure, identified through symbols like the Basileion on the pediment, represents the goddess Isis, merging Egyptian and Hellenistic artistic traditions.

Standing before it, you sense both majesty and silence: the stillness of stone and the lingering echo of ancient chisels. Over centuries, wind and sand have softened the details, but the Treasury’s glow—its rose-gold shimmer under shifting sunlight—remains untouched. Many visitors return at different times of day just to see how its colors transform.

Before reaching Petra’s grand theater, smaller tomb facades line the cliffs in tight, ascending rows, built during the 1st century A.D. These are mostly Pylon Tombs, marked by stepped crenellations and simple geometric elegance. Despite their modest scale, they form a striking architectural rhythm when viewed together.

Each tomb once served as both memorial and social space—some with benches for ritual banquets honoring ancestors. The clustering of these facades shows how dense and active Petra’s necropolises were, turning entire canyon walls into vertical cemeteries of art and remembrance.

Petra’s theater, cut directly into the rock in the early 1st century A.D., could once hold as many as 8,000 spectators. Its semicircular design echoes Roman architecture, though the original structure predated the Roman annexation of Nabataea in 106 A.D. Later, under Roman influence, it was expanded, even slicing through older tombs in the process.

Here, public life and performance met in dramatic harmony with the surrounding cliffs. The natural acoustics of the sandstone allowed voices to travel without amplification—a reminder that Petra was not just a city of merchants and priests but also of artists, musicians, and storytellers.

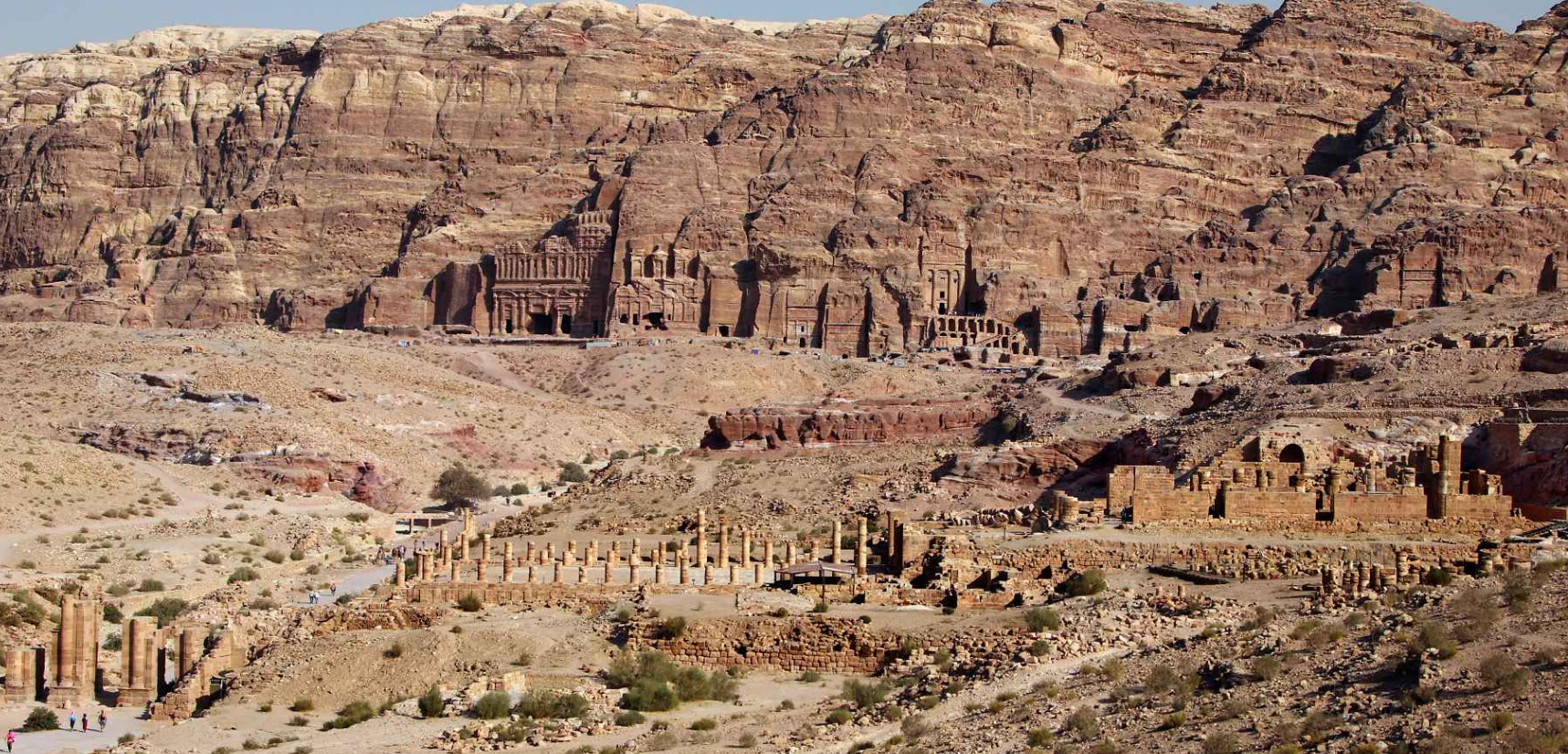

Among Petra’s most imposing structures stands the Urn Tomb, a monument that perfectly captures the Nabataean blend of grandeur and function. Built into the cliffs and facing the city’s heart, it is thought to have belonged to one of Petra’s kings. Like many large tombs here, it wasn’t merely a resting place—it was a complex. Surrounding courtyards, columned walkways, cisterns, and ceremonial rooms formed an architectural ensemble that turned memorial worship into a public ritual.

Centuries later, during the Byzantine era, the Urn Tomb took on a new life when it was converted into a Christian church in the 5th century. This transformation from royal mausoleum to house of worship embodies Petra’s layered story—where faiths and civilizations succeeded one another without erasing what came before. Even today, faint carvings and arches reveal traces of that Christian chapter against the older Nabataean backdrop.

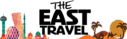

High above the valley, carved into the Jabal al-Khubtha rock face, rise the Royal Tombs—a sequence of massive facades that overlook the ancient city center. They are sometimes mistaken for palaces due to their elaborate ornamentation and monumental scale. Among them, the Palace Tomb, stretching nearly 49 meters across, commands attention with its layered columns and rhythmic symmetry.

These tombs form one of Petra’s most dramatic panoramas, especially at dusk when the sandstone glows deep crimson. Standing before them, you can imagine ancient processions ascending the steps, bearing incense and offerings, while the fading light turned the facades into mirrors of fire. The Royal Tombs are not just monuments to kings; they are Petra’s visual crown, watching over everything below.

The heart of Petra, known as the city center, spreads out beneath towering cliffs. Here, the monumental Great Temple Complex dominates the view, with the Royal Tombs etched into the western slope beyond. This was once the ceremonial and administrative nucleus of Nabataean life—a place where trade, politics, and ritual converged.

Walking through the center today, with columns lying scattered and stairs leading nowhere, you can still sense the grandeur of its former design. Scholars believe it hosted large public gatherings and possibly royal events, combining architecture with spectacle. The scale alone hints at a kingdom that valued both artistry and order.

Despite its name, the so-called Great Temple was not used primarily for religious purposes. Instead, it served as a grand civic and ceremonial hall—perhaps a royal assembly or court of state. Construction began toward the end of the 1st century B.C., and the building underwent multiple expansions and renovations in the following decades.

What remains today are rows of columns, fragments of ornate capitals, and wide staircases that once framed the temple’s entrance. Some of its architectural details suggest Hellenistic and Roman influences, yet its spirit remains uniquely Nabataean. The Great Temple stands as evidence that Petra’s rulers saw no boundary between political authority and artistic expression—they built power into beauty itself.

At the far end of the Colonnaded Street stands Qasr al-Bint Far’un, meaning “Castle of the Pharaoh’s Daughter.” Despite its name, this structure was no royal residence—it was Petra’s main temple dedicated to its chief deity, likely Dushara, the god of the mountains. Bedouin legends gave it its current romantic name, adding another layer of myth to its history.

This massive sandstone building was constructed using a combination of finely carved blocks and rougher masonry, an unusual mix that has allowed it to endure centuries of earthquakes and erosion. At its entrance once stood a grand triple-arched gate, marking the boundary of the sacred precinct. Standing before it today, you can almost hear the echo of priests’ footsteps and the faint resonance of ancient hymns rising toward the cliffs.

Before reaching the High Place of Sacrifice, visitors encounter two striking monoliths—stone obelisks over six meters tall, entirely chiseled out of the mountain itself. These monuments, known as nefeshes, were likely dedicated to rock deities or erected as memorials to deceased craftsmen who once worked in the nearby quarry.

The craftsmanship here is astonishing: each block freed from the living rock yet still rooted in it. The symmetry and scale speak to the devotion the Nabataeans held for their gods, as well as for the stone that defined their entire civilization. The silence around these obelisks, broken only by wind, feels almost sacred—a stillness that transcends time.

The High Place of Sacrifice, perched atop Jabal al-Madhbah at about 1,072 meters, offers one of Petra’s most spectacular panoramic views. Reached by a steep, winding path, the site rewards the climb with both history and horizon. It was likely dedicated to Dushara, the main deity of the Nabataeans, and served as a venue for ritual offerings and religious banquets.

At the summit, visitors find the west-facing altar, sometimes called the “god’s throne,” carved directly from the stone plateau. Channels run along its edges, possibly used to drain sacrificial liquids. Yet despite its name, the atmosphere here is serene. The view stretches across endless sandstone ridges, making it easy to understand why ancient people chose this height for communion with the divine.

Descending from the heights leads into Wadi Farasa East, a gentler and greener valley known to early explorers as the “Garden Valley.” In the spring of 1904, the German theologian and archaeologist Gustaf Dalman coined the name after discovering a surprisingly lush oasis here. Among its cliffs stands the Garden Triclinium, a rock-cut chamber fronted by graceful columns, once used for commemorative feasts honoring the dead.

Even today, the valley retains its calm, garden-like feel. It’s easy to picture Nabataean families gathering here during spring festivals, surrounded by the scent of desert blooms. The soft echoes of birds and the rustle of wind through the canyons lend a poetic quietness that contrasts beautifully with Petra’s monumental core.

Further along lies the Soldier Tomb Complex, named for the faint relief of a man in armor sculpted on its facade. Built in the later part of the 1st century A.D., this imposing mausoleum once formed part of a grand architectural ensemble complete with a colonnaded courtyard, triclinium, and auxiliary buildings.

The detail and proportion of this structure reveal a late period of Nabataean artistry, when Roman influences were blending with older traditions. The Soldier Tomb feels almost theatrical—its columns tall and commanding, its doorway dark and silent, as if guarding centuries of memories within.

Directly opposite the Soldier Tomb stands the Colorful Triclinium, often regarded as one of Petra’s most elaborate ceremonial chambers. This space, adorned with swirling sandstone hues of red, gold, and violet, once hosted ritual banquets in honor of the dead. The walls, now bare, were originally coated with stucco and richly painted, turning the chamber into a dazzling interior masterpiece.

When sunlight filters in, the natural mineral colors come alive—an effect so vivid that it feels almost supernatural. It’s one of those places where visitors realize that Petra’s beauty was never limited to its facades; the interiors, too, were once filled with artistry, music, and sacred purpose.

Finally, beyond winding mountain paths and quiet plateaus, stands Ad Deir, known as “The Monastery.” Despite its name, this was not a monastic site but rather a monumental temple or sanctuary. Its facade—47 meters wide and 48 meters high—echoes the design of the Treasury but in even larger, more powerful proportions.

A carved cross discovered inside during Byzantine times gave rise to its current name, yet scholars believe the building originally honored King Obodas I, who was deified after his death. Standing before Ad Deir, the immensity of its stone face and the silence of the surrounding cliffs create a sense of awe that words struggle to capture. Many travelers consider this the most moving spot in all of Petra—a fitting finale to a journey through one of humanity’s greatest achievements in stone.

The best views of Petra are not merely visual—they’re emotional, historical, and deeply human. Each monument reflects the genius of a civilization that thrived where few could, shaping beauty from hardship and leaving behind a city that still glows like a memory carved into time itself.