Few nations combine ancient memory and modern identity as gracefully as Jordan. This small Middle Eastern kingdom, officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, sits quietly at the meeting point of three continents—Asia, Africa, and Europe—where the past still whispers through every stretch of desert and every carved stone. It’s a place where biblical lands and Roman ruins coexist with lively cafés in Amman, and where hospitality remains more than custom—it’s a way of life.

Despite its limited natural resources, Jordan has built stability and openness in a region often marked by turbulence. Its strength lies not in oil, but in its people—their resilience, education, and deep respect for heritage. Travelers come to float in the otherworldly Dead Sea, to wander through the rose-colored canyons of Petra, and to feel the vast silence of Wadi Rum. Yet beyond its scenic wonders, Jordan reveals something deeper: a balance between tradition and progress, faith and modern governance, desert solitude and city vitality.

To understand Jordan is to trace human civilization itself—from the kingdoms of Moab and Edom to the Nabateans, Romans, and Ottomans, right up to the independent monarchy that guides it today. This is a land where every sunrise seems to cast light on both history and hope, where continuity feels almost tangible. Jordan isn’t just a country to visit; it’s a country to study, to remember, and, for many, to fall quietly in love with.

Jordan sits at a three-continent junction—Asia, Africa, and Europe—nestled in the Levant on the East Bank of the Jordan River. It shares borders with Saudi Arabia to the south and southeast, Iraq to the east, Syria to the north, and both Israel and the West Bank of Palestine to the west. The Dead Sea forms part of its western edge, while the country’s southern fingertip touches the Red Sea for 26 kilometers (16 miles), giving access to the port of Al-ʿAqabah. Amman, the capital and largest city, is Jordan’s beating heart—its political seat, commercial hub, and cultural center rolled into one.

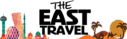

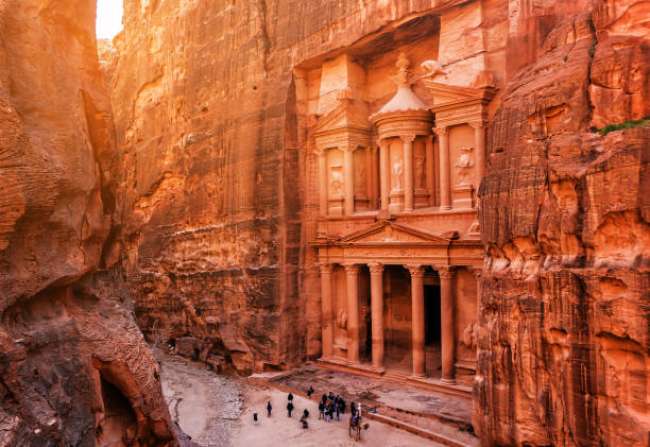

Jordan may be youthful as a state, yet the soil it occupies is among the most storied on Earth. Separated from ancient Palestine by the Jordan River, this landscape features in sacred narratives and classical histories alike. Within today’s borders lie the lands of Moab, Gilead, and Edom, alongside the rose-red marvel of Petra—capital of the Nabatean kingdom and later a Roman provincial centerpiece, Arabia Petraea. The traveler Gertrude Bell once called Petra a fairy-tale city, and even that feels like an understatement when dusk lights the sandstone into ember-glow. From centuries under the Ottoman Empire to the British Mandate after World War I, the polity that would become Jordan claimed full independence in 1946. Since then, the country has been viewed as one of the more politically liberal Arab states. Though it faces the same regional storms as its neighbors, Jordan’s leadership has consistently articulated a preference for stability and peace.

Amman—whose earliest name links back to the Ammonites, who set their capital here in the 13th century BCE—later became known as Philadelphia, member of the Roman Decapolis. Today the city is a crossroads of highways, ideas, and people, a transportation and trade nexus that doubles as one of the Arab world’s vibrant cultural capitals.

Land: Setting and Borders

Slightly smaller than Portugal, Jordan is hemmed by Syria to the north, Iraq to the east, Saudi Arabia to the southeast and south, and Israel plus the West Bank to the west. The West Bank, lying just west of the Jordan River, was under Jordanian administration from 1948 until 1967; in 1988, Jordan formally renounced claims to that territory. To the southwest, the kingdom’s 26-kilometer (16-mile) window to the sea opens onto the Gulf of Aqaba, where Al-ʿAqabah—Jordan’s sole port—links the country to global trade lanes.

Relief: Desert Tables, Upland Ridges, and the Rift

From east to west, Jordan’s surface unfolds in three major bands: a broad desert, a belt of uplands east of the Jordan River, and the dramatic trench of the Jordan Valley—the northwestern reach of the vast East African Rift System. The desert, mostly part of the Syrian Desert and an offshoot of the greater Arabian Desert, sprawls over more than four-fifths of the national territory. Its northern stretches are strewn with basaltic lava and black stone; to the south, wind-carved sandstone and granite outcrops dominate. Erosion—especially by wind—has sculpted mesas, buttes, and gravel plains into austere beauty. Westward, the uplands lift to a rugged escarpment overlooking the rift, standing 600–900 meters (2,000–3,000 feet) on average and rising to about 1,754 meters (5,755 feet) at Mount Ramm in the south. Here, layers of sandstone, chalk, and limestone shoulder up beside flint and, farther south, zones of igneous rock.

At the rift’s floor, the Jordan Valley plunges to extraordinary lows—reaching roughly 430 meters (1,410 feet) below sea level at the Dead Sea, the planet’s lowest continental point. The contrast between the airy uplands and this saline basin is as stark as any geography textbook could hope to illustrate.

Drainage: Rivers, Wadis, and a Saline Inland Sea

The Jordan River, about 300 kilometers (186 miles) long, snakes southward, gathering waters from Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee), the Yarmūk River, and seasonal streams tumbling off the plateaus into the Dead Sea. The valley’s lower soils are saline, and the Dead Sea’s shores spread into salt marshes where little can take root. South of the sea lies Wadi al-ʿArabah (Wadi al-Jayb), a near-empty corridor believed to hold mineral potential beneath its blistered flats.

In the northern highlands, several perennial valleys run west toward the Jordan. Around Al-Karak, streams bend west, east, and north depending on the slope; south of Al-Karak, intermittent channels head east toward the Al-Jafr Depression, carrying the memory of winter rains across thirsty ground.

Soils: Alluvial Fans and Upland Washes

Jordan’s most promising soils lie along the Jordan Valley and southeast of the Dead Sea. In both places, topsoil built from alluvium furnishes pockets of fertility—the valley accumulates sediments in wide alluvial fans that unfurl over marl, while southeast of the Dead Sea the uplands’ washes deliver fine material down-slope after rains. In a land where aridity is the rule, these sediment gifts are quietly transformative.

Climate across Jordan

Jordan’s climate shifts from Mediterranean in the west to desert across the east and south, but aridity is the constant thread. The nearby Mediterranean sets the background rhythm, while altitude and continental air masses remix the local tune. In the north, Amman averages roughly 8–26 °C (46–78 °F) month to month; far to the south, Al-ʿAqabah warms to about 16–33 °C (60–91 °F). Prevailing winds are typically westerly to southwesterly. Then come the khamsin episodes—hot, dry, and dust-laden blasts off the Arabian Peninsula—most common in early and late summer. They can grip the country for days, only to yield abruptly when winds swing and a cooler air mass sweeps in.

Rain falls mainly in the short, cool winters. Totals taper from about 400 mm (16 inches) in the northwest near the Jordan River to less than 100 mm (4 inches) in the south. East of the river, upland stations see ~355 mm (14 inches) annually; the valley averages ~200 mm (8 inches), and the desert receives a quarter of that. Snow and frost sometimes visit the uplands, whereas the rift valley rarely sees either. As cities swell, water scarcity has sharpened into one of Jordan’s defining policy challenges—touching households, farms, and industry alike.

Plant and Animal Life

Jordan’s flora divides into three broad types: Mediterranean scrub and woodland, steppe grasslands, and sparse desert growth. In the uplands, Mediterranean species weave dense thickets with scattered small trees. Eastward, across the steppe, grasses dominate and wormwoods (Artemisia) are common, while isolated shrubs—like lotus fruit and the Mount Atlas pistachio—dot the plains. In the desert proper, vegetation hugs depressions and the flanks of wadis, bursting briefly after modest winter rains before heat reins everything in.

Forested land is scarce, mainly clinging to the rockier highlands. Centuries of cutting and grazing reduced canopy cover, yet patches endure. Government-led reforestation programs distribute seedlings to farmers and encourage conservation on private and communal lands. Among upland trees are the Aleppo oak (Quercus infectoria), kermes oak (often identified regionally as Q. coccinea), Palestinian pistachio (Pistacia palaestina), Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), and eastern strawberry tree (Arbutus andrachne). Wild olives pepper slopes, and the Phoenician juniper (Juniperus phoenicea) persists where rainfall dips. The national flower, the black iris (Iris nigricans), blooms like a secret kept by spring.

Wildlife ranges from ibex and wild goats in gorges and around the ʿAyn al-Azraq oasis to hares, foxes, jackals, wildcats, hyenas, wolves, and the occasional gazelle or elusive leopard in rougher country. Reptiles, scorpions, and centipedes are common in arid zones. Raptors include golden eagles and vultures, while game birds run to pigeons and partridges—each one adapted to the sharp gradients of terrain and climate.

People

Ethnic Composition

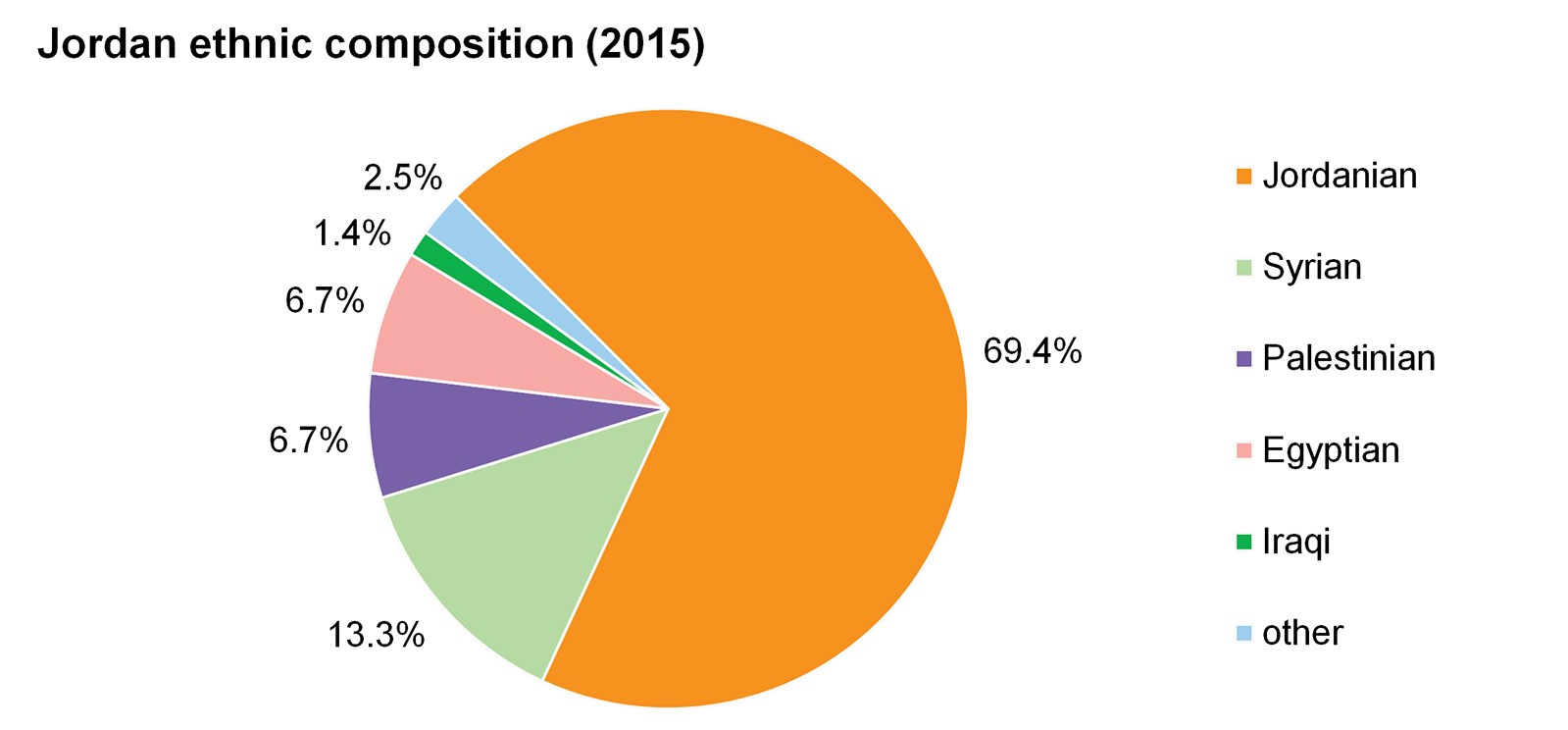

The overwhelming majority of residents are Arabs—principally Jordanians and Palestinians—with a significant Bedouin heritage that once formed the dominant indigenous population prior to the mid-20th-century refugee influxes following the Arab–Israeli conflicts of 1948–49 and 1967. Communities of Syrians displaced by the Syrian Civil War and Iraqis arriving after both the Gulf War and the Iraq War also live in Jordan, adding to the country’s mosaic. Smaller minorities include Circassians—often called Cherkess or Jarkas—and Armenians, alongside a modest Turkmen presence (speaking older Turkmen or Azeri variants).

Historically, many Muslim and Christian Arab families traced their lineage to broad tribal confederations: northern Arabian Qaysī (also called Maʿddī, Nizārī, ʿAdnānī, or Ismāʿīlī) and southern Arabian Yamanī (Banū Kalb, Qaḥṭānī). While only a few communities still actively maintain this Qaysī–Yamanī distinction, the echo of that old social map can still be heard in stories, identity, and sometimes in local alliances.

Languages

Arabic is the official and near-universal language. Everyday speech follows Levantine dialects familiar across Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria—mutually intelligible in markets and living rooms—while Modern Standard Arabic, taught in schools and used in formal settings, stays close to Classical Arabic. Most Circassians speak Arabic in daily life, though Adyghe survives in community settings, and Armenian persists in enclaves. Bilingualism and assimilation into Arabic are common across minority groups, a testament to the centripetal pull of media, schooling, and urban work.

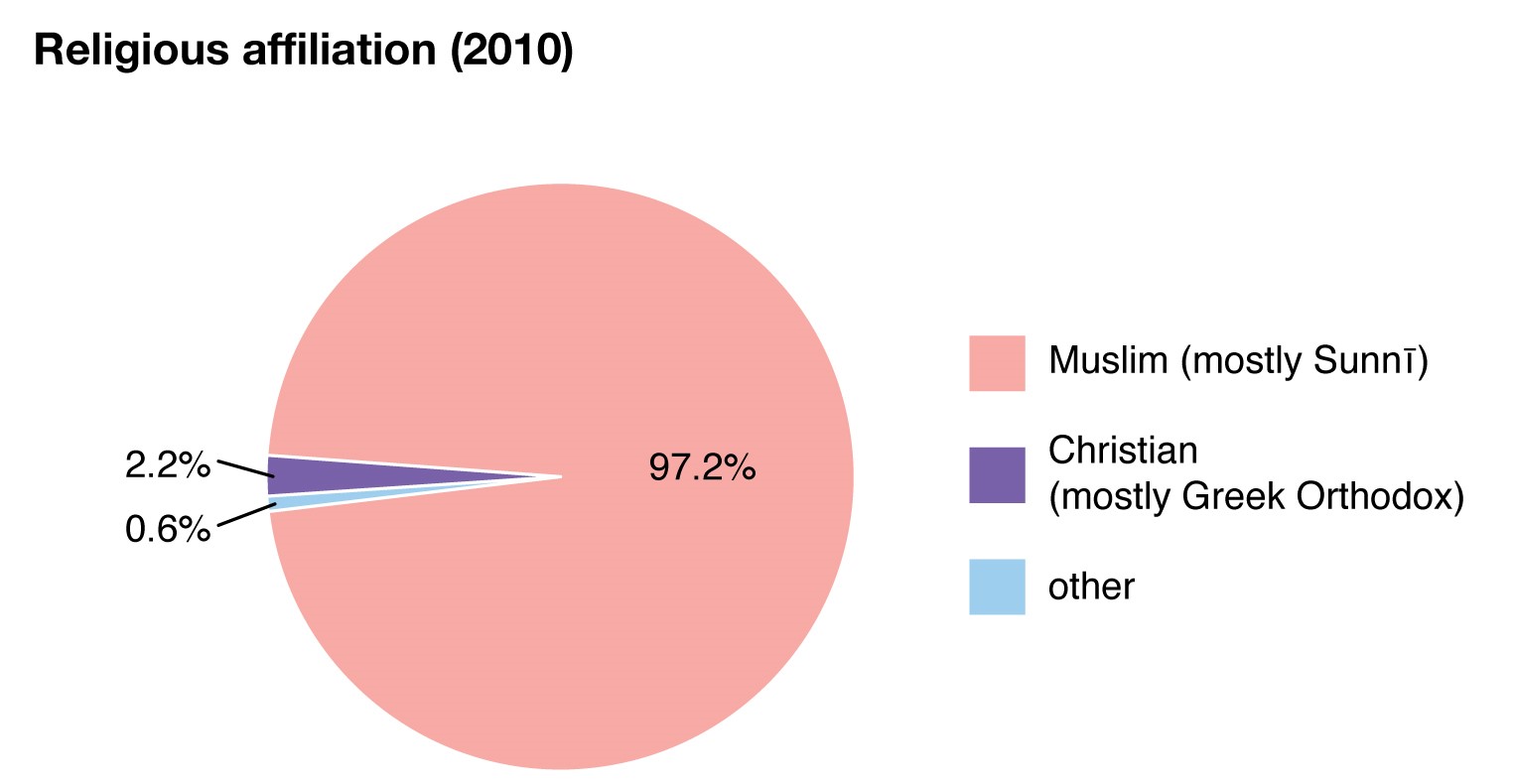

Religion

Most Jordanians are Sunni Muslims. Christians form the largest minority religious community, with roughly two-thirds belonging to the Greek Orthodox Church. Others include Greek (Melkite) Catholics of the Byzantine rite, Roman Catholics led by a patriarch appointed by the pope, and the smaller Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch (Syrian Jacobite), which maintains Syriac in its liturgy. Many non-Arab Christians are Armenians, largely aligned with the Armenian Apostolic (Gregorian) Church, while an Armenian Catholic minority also exists. Protestant congregations represent converts from other Christian traditions.

Smaller groups include the Druze—an offshoot of Ismāʿīlī Shiʿism—living mainly in and around Amman, and a modest Bahāʾī community in Al-ʿAdasiyyah in the Jordan Valley. The Circassians are overwhelmingly Sunni; closely related Chechens (Shīshān), whose ancestors migrated from the Caucasus in the 19th century, form another small but visible thread in Jordan’s social fabric.

Economy

Jordan’s economy is compact yet diversified. Trade and finance together approach a third of GDP; transportation and communications, public utilities, and construction make up about a fifth; and mining plus manufacturing account for a similar slice. Remittances sent home by Jordanians working abroad are crucial for foreign exchange, smoothing shocks and supplementing domestic earnings.

Government services remain central—both as an employer and as a spender—reflecting the country’s history and its role as a regional shelter in times of upheaval. Since the mid-1990s, pressures from recession, rising debt, unemployment, and the limited scale of the domestic market have kept Jordan reliant on foreign assistance. Agricultural volatility, constrained capital, and repeated refugee inflows further complicate planning. Market-oriented reforms began in earnest in 1999: WTO accession followed in 2000; portions of state firms were privatized; and agreements with the IMF and World Bank aimed to deepen the private sector while relieving external debt.

Geopolitics leaves fingerprints all over the national balance sheet. Before the 1967 Six-Day War, Jordan’s economy was resilient and expanding; the West Bank then contributed roughly a third of domestic income. Growth slowed but continued under state planning. During the Iran–Iraq War (1980–88), trade via Jordan’s port at Al-ʿAqabah surged as Iraq sought alternative access; later, sanctions on Iraq—formerly Jordan’s key trading partner—threatened to upend the economy. Emergency assistance and capital brought by returning Palestinians from Kuwait in 1991 helped stabilize conditions. In 2003, the influx of people fleeing Iraq stimulated construction, and Jordan evolved into a logistics and service base for reconstruction efforts next door. Even with reform, the state remains a dominant economic actor, orchestrating investment and employment in a challenging neighborhood.

Agriculture

Only a sliver of Jordan’s land is arable, so the country imports staple foods to meet demand. Rain-fed uplands host wheat and barley. Along the irrigated Jordan Valley, citrus groves share space with stone fruits, potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers, and olives. Pasture is scarce; despite artesian wells expanding some grazing zones, many former pastures have been converted to orchards, while other tracts degraded to the point of barely supporting herds. Sheep and goats are the mainstays, supplemented by smaller numbers of cattle, camels, horses, donkeys, and mules. Poultry operations help fill protein gaps, especially nearer to cities.

Resources and Power

Jordan’s mining profile features large deposits of phosphates and potash, plus limestone and marble. The subsurface inventory also lists dolomite, kaolin, and salt, with newer finds of barite (a key barium ore), quartzite, gypsum (valued as soil amendment and in cement), and feldspar. Copper, uranium, and shale oil are believed to exist in unexploited quantities. Oil is negligible, but modest natural gas reserves in the eastern desert help diversify inputs. In the early 2000s, a pipeline from Egypt began supplying gas to Al-ʿAqabah, bolstering energy security.

Electric power is produced predominantly at thermal plants—most historically oil-fired—knit together by a national grid completed in the early 21st century to connect major cities and towns. Beyond electrons, water scarcity looms as an equally strategic resource issue. Overuse of the Jordan and Yarmūk Rivers and heavy withdrawals from aquifers spurred cooperation and conflict in equal measure. In 2000, Jordan and Syria secured funding for a dam on the Yarmūk; construction of the Waḥdah (“Unity”) Dam began in 2004 to store water for Jordan and generate electricity for Syria—an emblem of how resource stress shapes regional diplomacy.

Manufacturing

Industry clusters around Amman. Heavy-industry pillars include phosphate extraction, petroleum refining, and cement. Food processing, apparel, and a spread of consumer goods make up the broader manufacturing base. Export-processing areas and free zones have helped knit local production into global retail and supply chains.

Finance

The Central Bank of Jordan issues the dinar and supervises a banking system that includes domestic and foreign institutions plus specialized credit providers. The state retains meaningful stakes in the largest mining, industrial, and tourism enterprises, mirroring the mixed-economy approach. The Amman Stock Exchange (formerly the Amman Financial Market) is among the region’s larger venues, channeling savings into public and private ventures.

Trade

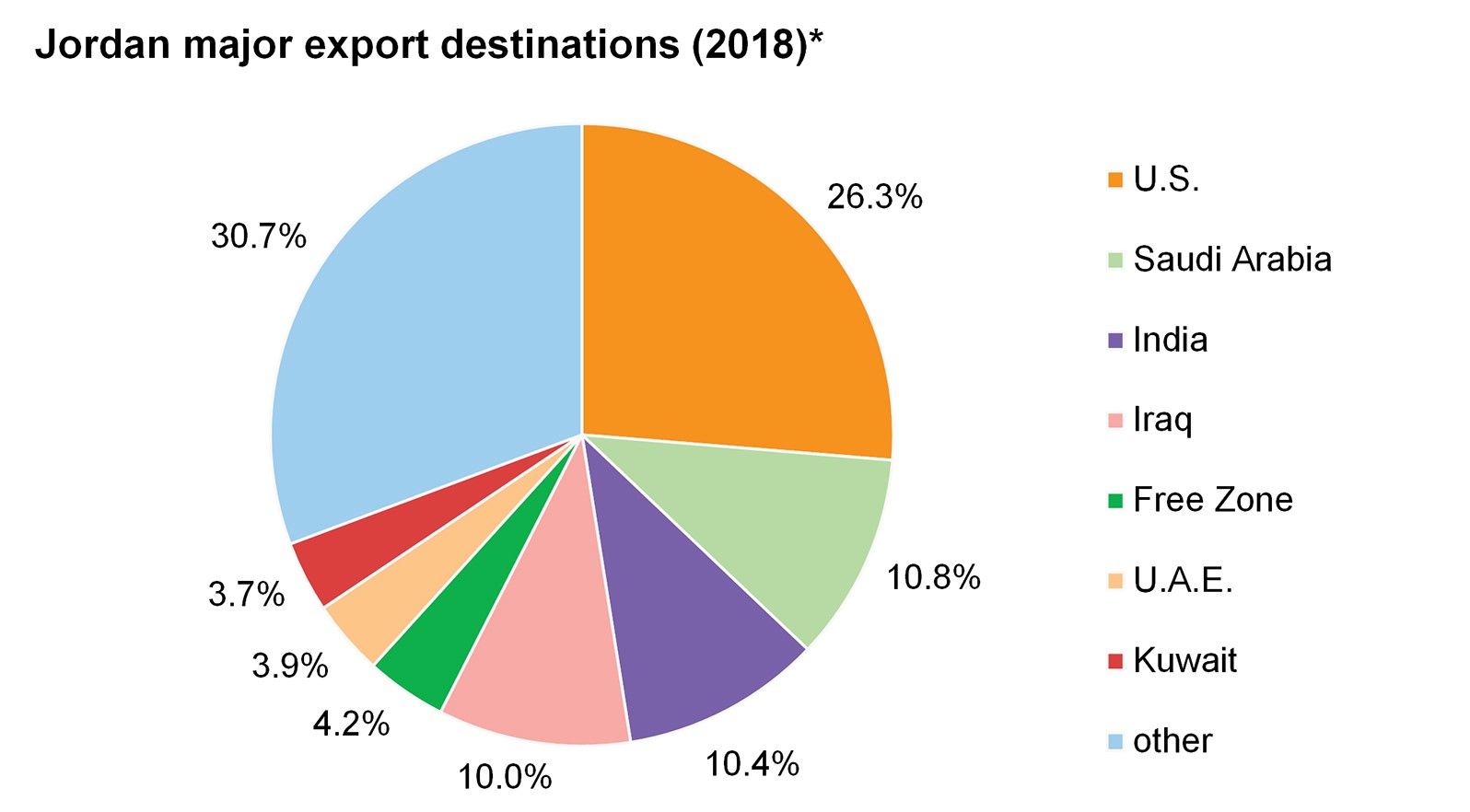

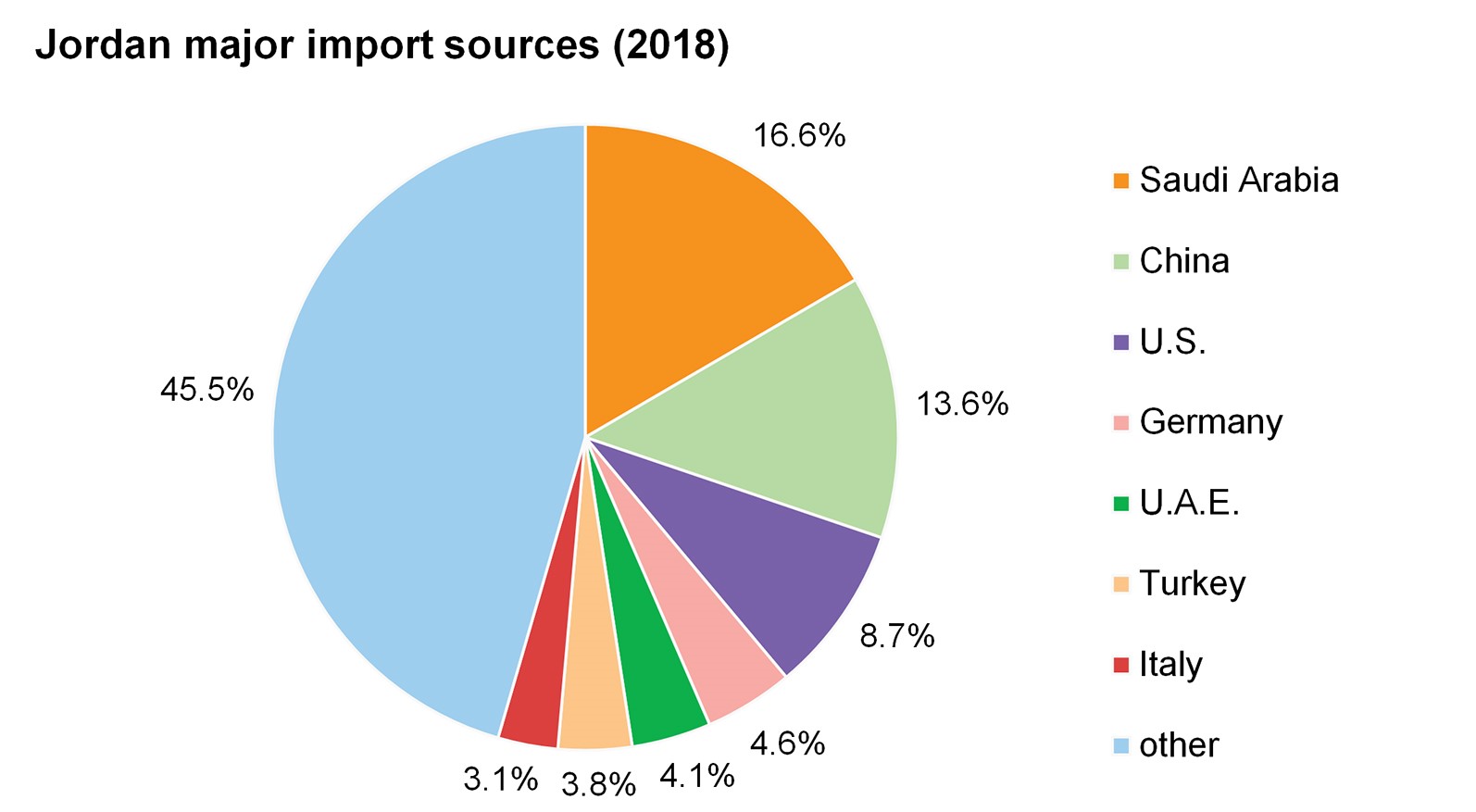

Top exports include clothing, chemicals and derivatives, and potash and phosphates. Imports are led by machinery and equipment, crude petroleum, and food products. Major import sources are Saudi Arabia, the United States, China, and the European Union; primary export destinations include the United States, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. A bilateral free-trade agreement with the United States was signed in 2000. Although export values have trended upward, they typically lag imports; the gap is bridged by grants, loans, and capital transfers. Tourism receipts, worker remittances, central bank investment income, and periodic subsidies from partner governments help offset the persistent trade deficit.

Services

Services—public administration, defense, retail, hospitality, and more—are Jordan’s single largest economic component by both value and employment. Geography and geopolitics, combined, push military outlays above global averages. Tourism promotion has been vigorous since the mid-1990s; visitors from around the world come for biblical sites, the Dead Sea, the canyons and dunes of Wadi Rum, and Petra’s hypnotic facades (a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1985). Travel income, largely in foreign currency, plays a crucial role in narrowing external imbalances.

Labour and Taxation

Jordan has experienced significant skilled-labor outflows, especially in the early 1980s when hundreds of thousands left for opportunities in Gulf states. The tide has eased somewhat—both because of improved domestic prospects and fewer foreign openings. Men make up the majority of the workforce; women constitute roughly one-seventh—an area of active policy interest given the growth potential in higher female participation. The state directly employs a large share of workers. Official unemployment remains a structural concern, though per capita income has generally climbed over time.

Labour unions and employer associations are legal but not especially powerful; state mechanisms often mediate disputes. Around half of government revenue comes from taxes, with indirect levies outstripping direct income taxes despite reforms to broaden and rebalance the system. Investment-friendly exemptions aim to encourage savings and attract foreign capital, while easing the movement of profits and principal.

Transport and Telecommunications

Jordan’s road network—main, secondary, and rural—covers the country with primarily paved links. Signature arteries include the Amman–Jarash–Al-Ramthā highway connecting to Syria; the Amman–Maʿān route leading south to Al-ʿAqabah; and the Desert Highway through Al-Mudawwarah to Saudi Arabia. The Amman–Jerusalem route via Nāʿūr serves as a well-traveled tourist corridor. Rail includes the Hejaz–Jordan Railway from Darʿā in the north through Amman to Maʿān, and the Aqaba Railway Corporation’s southern line tying phosphates to the port, with connections near Baṭn al-Ghūl; links also extend from Darʿā to Damascus.

Royal Jordanian, the national carrier, maintains international service. Queen Alia International Airport, south of Amman near Al-Jīzah, opened in 1983 as the main gateway; Amman and Al-ʿAqabah support additional international traffic.

Telecom reform in the 1990s transformed access. The state-owned Jordan Telecommunications Corporation—once the sole provider—was privatized in 1997. Mobile adoption surged past fixed lines, and internet use expanded rapidly, reshaping commerce, media, and daily life from the capital outward.

Government and Society

Constitutional Framework

Jordan’s 1952 constitution—the latest in a series of charters before and after independence—strengthened executive responsibility while delineating a constitutional, hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary form. Islam is the official religion, and Jordan is defined as part of the wider Arab ummah. The king remains the ultimate authority, with influence over executive, legislative, and judicial spheres. A prime minister—appointed by the king and subject to parliamentary approval—heads the cabinet, which coordinates ministries and sets general policy.

The bicameral National Assembly comprises an appointed Senate (Majlis al-Aʿyan) and an elected House of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwwāb). Seats are reserved for Christians and Circassians in the lower house. Jordan’s parliamentary life has seen interruptions—prorogations, suspensions, and electoral reforms—but the institution remains a central arena for politics, debate, and accountability.

Local Government

Twelve governorates (muḥāfaẓāt) subdivide the country into districts and subdistricts, each administered by officials under the Ministry of the Interior. Cities and towns elect councils and are headed by mayors, mixing local voice with central oversight to deliver services and manage growth.

Justice

An independent judiciary is guaranteed constitutionally, though judges are appointed and dismissed by royal decree upon recommendation of the Justices Council. Courts fall into three families. Regular courts include magistrates, first-instance tribunals, and appellate and cassation courts (with the highest seated in Amman). A Special Council (Diwān Khāṣṣ) interprets law and rules on constitutional matters. Religious courts—Sharīʿah for Muslims and separate courts for non-Muslims—handle personal status. Specialized courts oversee land, government property, municipalities, tax, and customs, reflecting the practical needs of administration.

Political Process

Voting begins at age 18. Party life has evolved in phases—parties were once banned, and a single mass organization functioned in the early 1970s before being abolished. Political liberalization in the late 1980s and early 1990s restored multiparty elections (1993 marked the first such polls since 1956). The Muslim Brotherhood, through the Islamic Action Front, has maintained a consistent, if minority, presence. While the monarchy remains the anchor of the system, electoral competition, civil society, and media debate add texture to public life.

Security

The Bedouin—renowned as formidable desert fighters—historically formed the backbone of the army and still hold prominent military roles. Service is voluntary, with enlistment from age 17. The armed forces include an army and an air force equipped with modern jets; a small navy performs coast guard duties on the Red Sea. The king serves as commander in chief, and the military traces lineage to the famed Arab Legion.

Health and Welfare

Jordan records an infant mortality rate lower than in several neighboring states, and infectious diseases have retreated with decades of public-health investment. Physician density has improved markedly. Government-run facilities anchor the system, though hospitals are concentrated in larger cities. A national health insurance framework offers medical, dental, and vision care at modest cost, with free services for the poorest households. Welfare, once mainly private and charitable, shifted to state supervision and coordination in the mid-1950s, expanding coverage and standardizing support.

Housing

Housing demand has long outstripped supply, especially in Amman and the eastern Jordan Valley. Surveys show many families making do with cramped, one-room dwellings. The Housing Corporation and the Jordan Valley Authority build for low-income households, and urban-renewal efforts in Amman and Al-Zarqāʾ have added and refurbished units. Outside the cities, shelter remains simple; a small number of Bedouin still pitch traditional black tents, an enduring emblem of mobility and desert heritage.

Education

Literacy is widespread, and more than half the population has completed secondary school or higher. Three school systems—government, private, and UNRWA (for Palestinian refugees)—operate under the Ministry of Education’s supervision. The structure is six years of elementary, three of preparatory, and three of secondary schooling. The ministry sets curricula, teacher qualifications, and standardized exams; it also provides free textbooks in government schools and enforces compulsory education through age 14. Higher education took off in the latter 20th century: the University of Jordan (1962), Yarmūk University (1976), and Muʾtah University (1981) led the way, with many more added in the 1990s. Agricultural and vocational institutes, a Sharīʿah seminary, and specialized nursing, military, and teacher colleges round out the landscape.

Daily Life and Social Customs

Jordan shares the cultural grammar of the Arab world, with family at its center. Rural Bedouin communities, though fewer as settlement increases, preserve traditions of hospitality, reciprocity, and oral artistry. In villages, extended families and agriculture shape the rhythm of days; in cities, galleries, theatres, cafés, and concert halls speak to an increasingly cosmopolitan taste. Cinema thrives in major towns. In Amman, younger crowds toggle between espresso and bandwidth in internet cafés—a small symbol of how the old and new coexist comfortably.

Cuisine leans on beans, olive oil, yogurt, and garlic. Two beloved dishes take pride of place at feasts and family milestones: musakhkhan—tangy chicken with sumac and onion over taboon flatbread—and mansaf, lamb or mutton with rice bathed in jameed (a tart yogurt sauce). Everyday tables carry khubz alongside grilled meats, stews, and vegetable dips, with cardamom coffee or sweet tea as constant companions.

Religious and national holidays piece together the calendar: the Prophet’s birthday (mawlid), the two ʿīds—Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha—and secular commemorations like Independence Day and the birthday of the late King Hussein.

The Arts of Jordan

Public and private initiatives sustain the arts through cultural centers in Amman, Irbid, and beyond, as well as through festivals that bring poetry, music, and performance to plazas and stages. Modern life has softened long-held religious cautions about figurative representation, and today alongside architecture, decorative arts, and handicrafts you’ll find painters and sculptors working in both representational and abstract modes. Manuscripts and mosques shine with calligraphy and geometric ornament, marrying spiritual resonance with strict design.

Tapestry, embroidery, leatherwork, pottery, and ceramics carry older aesthetics forward, and weaving—especially wool and goat-hair rugs in vibrant stripes—remains a living craft. Song is essential: villagers still keep repertoires for births, circumcisions, weddings, harvests, and funerals. Dabkah line dances, all thundering footfalls and communal energy, animate celebrations; the Bedouin sahjah is another favorite. The Circassian minority performs a striking sword dance among other Cossack-derived forms. A government-sponsored national troupe preserves and broadcasts these traditions on radio and television, ensuring the next generation knows the steps.

Jordan’s film industry is modest but ambitious. Its landscapes have drawn the world’s great directors to shoot here: Petra and Wadi Rum starred in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), giving cinema-goers unforgettable vistas and the kingdom a lasting place in movie lore.

Cultural Institutions

Amman’s museums chart coins, geology, stamps, Islam, folklore, and military history. The Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts curates contemporary Arab and Muslim works in painting, sculpture, and ceramics. Petra, Qaṣr ʿAmrah, and the archaeological site of Umm al-Rasass near Mādāba bear UNESCO World Heritage designation, and archaeological museums across the country knit together Jordan’s deep past with new discoveries—reminding visitors that this “young” nation stands atop one of humanity’s oldest and richest neighborhoods.