Fourteen years after it began, the Syrian Civil War remains one of the most haunting chapters of the modern Middle East. What started in 2011 as peaceful demonstrations calling for reform spiraled into a catastrophic multi-sided conflict that redrew alliances, shattered cities, and displaced millions. Today, Syria stands at a crossroads — caught between fragile recovery and the lingering shadows of war.

The fall of Bashar al-Assad in 2024 marked a turning point. For the first time in over five decades, Syrians are navigating their future without authoritarian rule, yet the challenges ahead are immense. Reconstruction is slow, foreign forces still occupy strategic zones, and millions continue to live as refugees or in makeshift camps.

Still, amid the rubble and silence, there are signs of renewal. Markets are reopening, schools are being rebuilt, and Syrians, both at home and abroad, are daring to imagine a country free from the violence that defined their lives for so long. This article revisits how the war began, the cost it exacted, who holds power today, and why — even in 2025 — the struggle for peace remains unfinished.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT-AFP

How Did the Syrian Conflict Begin?

Before the first protester took to the streets, Syria was already simmering with discontent. Economic inequality, rising unemployment, and decades of political repression under the Assad family had left many Syrians hopeless. In early 2011, inspired by uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, demonstrations began in the southern city of Daraa after a group of teenagers were arrested for painting anti-government slogans. The protests were small at first, calling merely for reform. But when security forces responded with bullets instead of dialogue, the movement spread nationwide.

By that summer, calls for democracy had hardened into calls for regime change. Assad labeled the protesters “terrorists,” and state forces launched brutal crackdowns. Ordinary Syrians began arming themselves — some out of anger, others out of desperation. Opposition groups emerged across the country, and soon what had begun as civil unrest escalated into a multi-sided war.

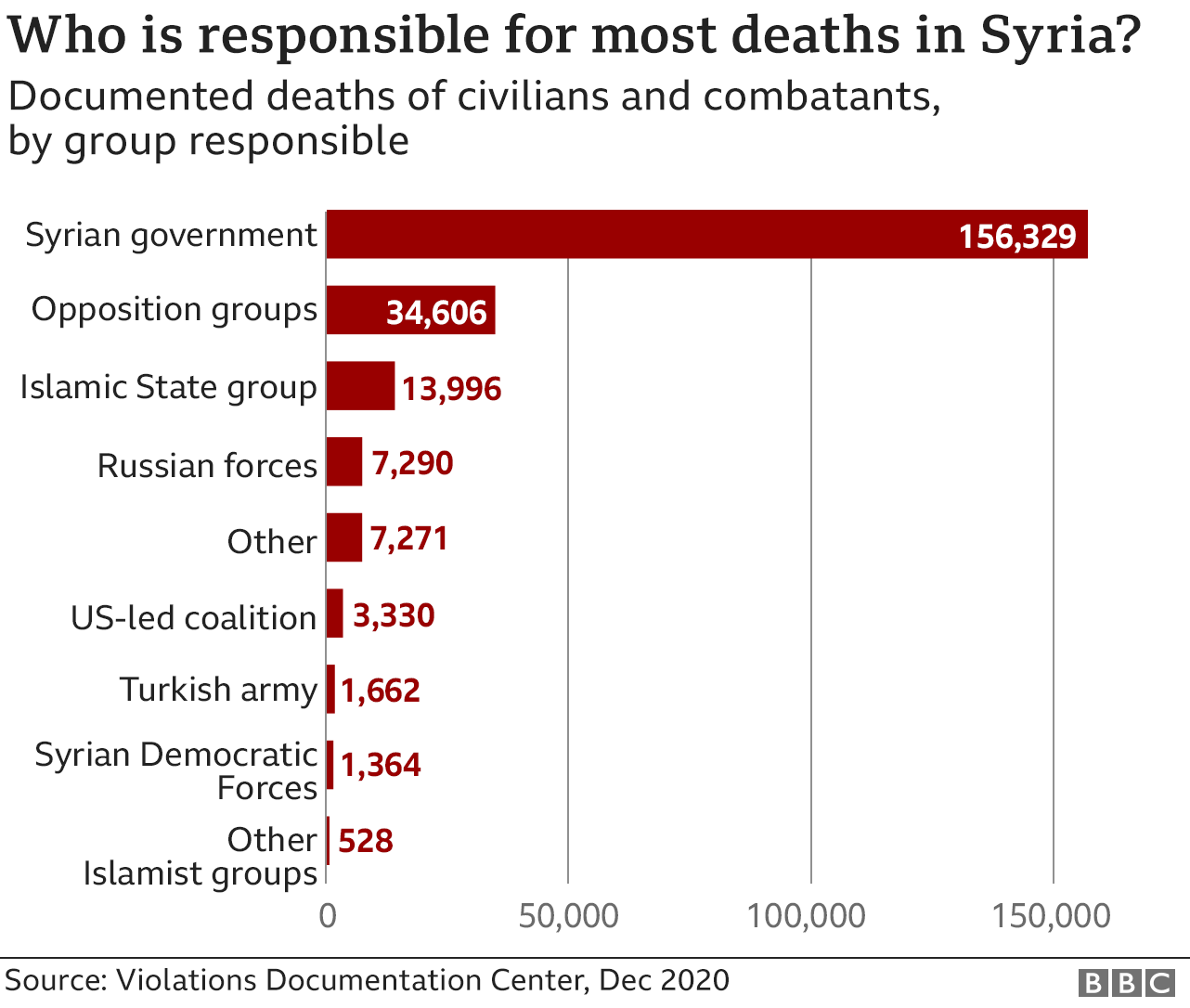

Foreign powers took notice. Iran and Russia intervened to support Assad, while Gulf states, Turkey, and Western countries backed different rebel factions. Over time, extremist organizations like ISIS and al-Qaeda exploited the chaos, adding another deadly dimension to the conflict. The war had evolved beyond a domestic struggle — it became a regional and global battlefield fought over Syrian soil.

IMAGE COPYRIGHT-REUTERS

The Human Cost

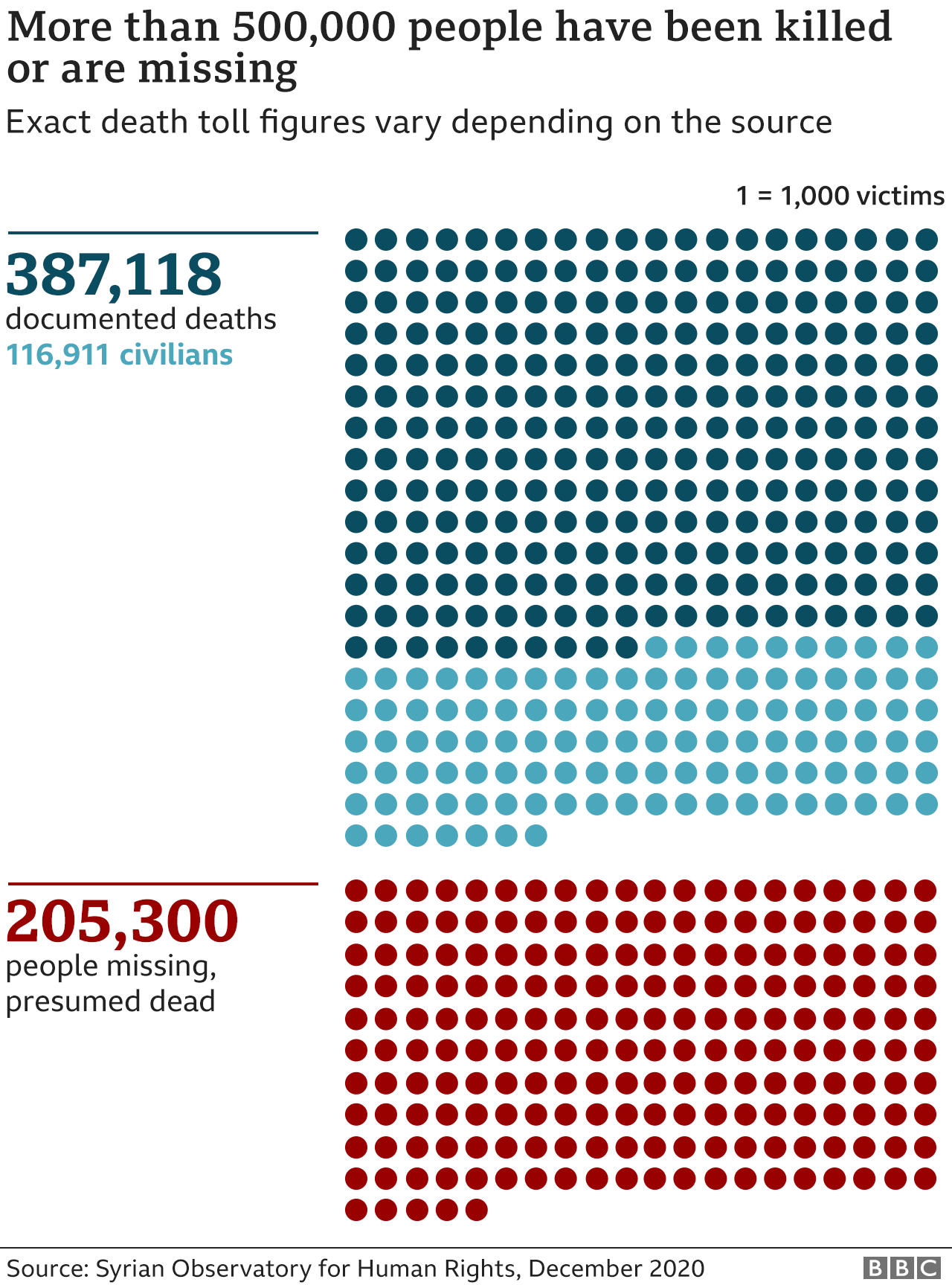

By 2025, the total human toll remains staggering.

Monitoring organizations estimate that between 580,000 and 610,000 people have been killed since 2011. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) and UN reports indicate that more than 120,000 civilians are among the dead, and over 100,000 individuals remain missing or presumed dead after years of detentions, disappearances, and mass graves.

Millions of others live with invisible wounds. The psychological impact — especially among children — has been described by UNICEF as a “silent emergency.” Generations have grown up knowing only conflict, displacement, and fear.

Cities such as Aleppo, Homs, and Raqqa, once cultural jewels, became battlegrounds. By 2025, reconstruction efforts are slowly returning life to their streets, but much of the old beauty remains buried under dust and twisted steel.

Foreign Powers and Their Role

Russia continues to play a decisive role in Syria’s transition. After Assad’s departure, Moscow struck agreements with the interim government to retain its air base at Hmeimim and naval facilities at Tartus. While it presents itself as a stabilizing power, Russia’s long-term presence ensures that it still influences Syria’s political future.

Iran, which spent billions propping up Assad, now faces waning influence but maintains allied militias and advisors in central and southern Syria. Meanwhile, Israel frequently conducts precision airstrikes against Iranian assets to prevent permanent entrenchment near its borders.

Turkey controls portions of the north, enforcing a buffer zone aimed at curbing Kurdish autonomy. Turkish-backed Syrian factions maintain checkpoints and administer border towns, while negotiations with Damascus remain tense but ongoing.

The United States and European nations have drastically reduced their direct involvement since 2023. American troops completed their drawdown from northeastern Syria in mid-2025, leaving small advisory groups to assist Kurdish-led security forces in containing ISIS remnants.

Despite these withdrawals, Syria remains under heavy international sanctions. The economy has collapsed, its currency has lost nearly 99% of its pre-war value, and unemployment exceeds 50%. For many Syrians, the fight for survival has replaced the fight for freedom.

The Displacement Crisis

Few wars in modern history have produced such massive displacement.

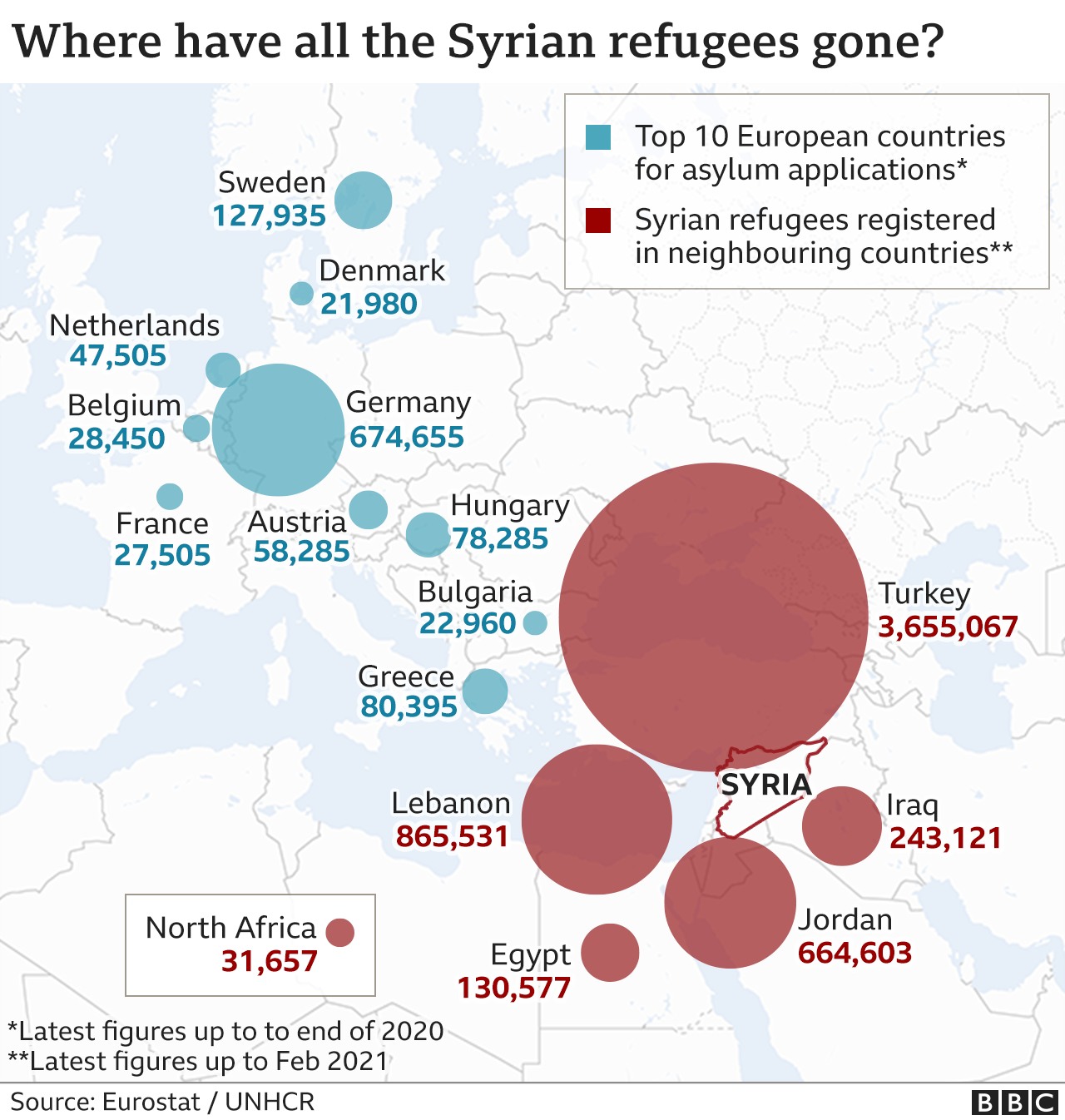

By 2025, nearly 6.8 million Syrians remain refugees abroad, while another 6.9 million are internally displaced. Neighboring countries — primarily Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan — still host the majority of refugees, though some have begun returning home under UN-sponsored voluntary repatriation programs.

Inside Syria, vast camps dot the landscape, particularly in the northwest. Many families have spent over a decade in tents, raising children who have never seen the cities their parents fled. Aid agencies report that over 17 million people inside Syria now rely on humanitarian assistance. Food insecurity affects roughly 70% of the population, and access to clean water and healthcare remains sporadic.

The 2023 earthquake in northern Syria and southern Turkey only deepened the suffering, destroying shelters and infrastructure in regions already ravaged by war. Humanitarian organizations continue to warn that without sustained funding, Syria could face one of the worst post-war recovery crises in modern history.

Who Controls Syria in 2025?

Although Bashar al-Assad’s rule ended in 2024, Syria remains a patchwork of competing authorities, uneasy alliances, and foreign military zones. The interim government in Damascus, led by a coalition of technocrats and former opposition figures, now controls most of the major urban centers — including Damascus, Homs, and parts of Aleppo. However, true sovereignty is far from complete.

The northwestern province of Idlib continues to be dominated by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a militant faction with deep roots in jihadist movements. Despite international pressure, HTS still administers the area through its civil arm, managing checkpoints, local councils, and relief distribution. Tensions remain high between HTS and other opposition groups, though a fragile ceasefire with government forces, negotiated by Turkey and Russia in late 2023, has prevented a new wave of large-scale fighting.

In the northeast, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) — primarily led by Kurdish forces under the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) — continues to operate semi-independently. Although Damascus and the AANES signed a limited coordination pact after Assad’s departure, disputes persist over oil revenue, local governance, and military control. Turkish troops and allied Syrian militias still occupy strips of borderland, effectively creating a long buffer zone between the Kurds and Turkey’s frontier.

Meanwhile, Iranian-backed militias maintain a strong presence in parts of Deir ez-Zor and southern Syria. Their activities remain a point of tension between Tehran, Israel, and the interim Syrian government. Frequent Israeli airstrikes throughout 2024 and 2025 have targeted weapons depots and command centers believed to house Iranian assets, often causing collateral damage among civilians.

In essence, Syria in 2025 is divided not by frontlines but by zones of influence — each shaped by foreign interests, local power brokers, and the delicate balance of survival after years of war.

The War’s Lasting Human and Economic Impact

The end of major hostilities did not bring peace of mind for ordinary Syrians. The war’s economic, psychological, and cultural wounds continue to deepen.

According to UN data published in early 2025, over 90% of Syrians now live below the poverty line, and the average monthly income in Damascus has dropped to the equivalent of $40–$50 USD. The country’s infrastructure remains shattered — only about half of hospitals and schools are operational, and many cities still resemble ghost towns.

Electricity shortages are routine, clean water is scarce, and fuel prices are beyond the reach of most families. The Syrian pound has stabilized slightly since Assad’s departure, but inflation remains catastrophic. Rebuilding costs are estimated to exceed $400 billion, a figure that dwarfs Syria’s annual GDP several times over.

Culturally, the losses are immeasurable. The once-proud souks of Aleppo, Hama’s ancient waterwheels, and the Roman ruins of Palmyra — all symbols of Syria’s rich past — remain partially or fully destroyed. UNESCO teams and Syrian archaeologists have begun limited restoration work, but progress is painfully slow due to lack of funding and lingering security risks.

Psychologically, the toll is equally severe. Millions of Syrians suffer from trauma, depression, or survivor’s guilt. Children born during the war have grown up amid displacement, loss, and instability. NGOs estimate that nearly three million Syrian children have never attended school, and many who did are now too old to resume formal education. This “lost generation” is one of the conflict’s most haunting legacies.

Humanitarian Situation and Refugee Crisis

Despite the cessation of large-scale fighting, Syria remains one of the world’s largest humanitarian emergencies. As of 2025, 17.3 million Syrians inside the country require humanitarian assistance, and over 7 million remain displaced abroad.

Turkey hosts approximately 3.1 million Syrian refugees, though it has tightened border control and reduced new entries. Lebanon, with its fragile economy, still shelters about 1 million Syrians, while Jordan houses around 670,000 registered refugees. Many others live in Iraq, Egypt, and across Europe — particularly in Germany and Sweden, which together have accepted over 1 million Syrians since 2015.

Return movements have been modest but steady. The UNHCR reports that around 700,000 refugees have returned to Syria since 2022, mainly to government-controlled areas. Yet most returnees face dire conditions: destroyed homes, lack of jobs, and restricted access to healthcare or education. The World Food Programme (WFP) warns that hunger affects over two-thirds of Syrian households, and the country’s agricultural output has fallen by nearly 60% compared to pre-war levels.

The healthcare system, battered by years of bombardment and sanctions, struggles to function. Medical professionals continue to emigrate, and medicine shortages are chronic. In some provinces, families rely on herbal remedies and smuggled pharmaceuticals to survive.

International sanctions — while aimed at pressuring remaining war profiteers and corrupt elites — have deepened the suffering of ordinary Syrians by limiting imports and freezing reconstruction funds. Critics argue that without a clear path toward economic rehabilitation, Syria’s humanitarian catastrophe will persist for decades.

Foreign Influence and Geopolitical Tensions

Even as Syria attempts to rebuild, it remains a chessboard for international powers.

Russia, having achieved most of its strategic goals, now seeks to transform its military presence into long-term economic influence. Moscow has secured control over several key energy and phosphate extraction sites and signed contracts for future port expansions along the Mediterranean coast.

Iran, though weakened by domestic unrest and sanctions, still views Syria as a vital corridor connecting Tehran to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Its continued deployment of militias and infrastructure projects in southern and eastern Syria has drawn ongoing Israeli retaliation.

Turkey remains cautious. President Erdoğan’s government continues to demand a permanent buffer zone along its border to prevent Kurdish consolidation, while maintaining a complex mix of cooperation and rivalry with Russia and the Damascus authorities.

Meanwhile, Western engagement has waned. The United States and European Union maintain sanctions but offer humanitarian funding through NGOs and UN agencies. Their direct military footprint is now minimal, limited mostly to counterterrorism operations against ISIS remnants near the Euphrates River valley.

The result is a delicate equilibrium — one where every external actor holds influence, yet none possesses full control. Syria’s sovereignty, for now, exists on paper more than in practice.

Will the Syrian War Ever Truly End?

After more than fourteen years, the guns have quieted, but peace is still a fragile illusion. The interim government faces monumental challenges: rebuilding shattered cities, repatriating refugees, reviving an economy strangled by sanctions, and reconciling communities divided by war.

UN-mediated peace talks in Geneva resumed in early 2025, focusing on drafting a new constitution and preparing for internationally monitored elections by 2026. While these developments offer glimmers of hope, skepticism remains high among Syrians who have witnessed countless broken promises over the years.

Experts agree that Syria’s path to recovery depends on one thing above all — stability. Without it, even the best political solutions will collapse under the weight of corruption, poverty, and foreign interference.

Yet there are signs of resilience. In Aleppo’s Old City, small cafés have reopened amid the rubble. Children once again play along the banks of the Barada River in Damascus. Farmers in Idlib and Daraa are cultivating wheat and olives for the first time in years.

These are small steps, but they mark the quiet persistence of a people who, despite unimaginable loss, refuse to surrender their homeland’s future.